Notes on the Inscription on the “Diker Bowl” (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

David F. Mora-Marín

davidmm@unc.edu

University of North Carolina

Chapel Hill

6/12/2021

In his The Maya Scribe and His World, Michael Coe introduced Mayanists to a myriad inscriptions on portable and monumental media alike. One of them, seen in Figure 1, was a carved stone bowl formerly in the collection of Mr. Charles Diker and Mrs. Valerie Diker, and now in the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accession Number 1999.484.3 (Doyle 2016). The bowl is carved out of “indurated limestone with red veins,” and constitutes an example of a spouted vessel that may have been “used to froth cacao liquid at the moment of serving” (Fields and Reents-Budet 2005:202).[1] It was estimated to date to the “Proto-Classic” period by Coe (1973:26), between “A.D. 0-300,” and to the late Late Preclassic period by Fields and Reents-Budet (2005:202), between ca. “50 BC-AD 200.”

Figure 1. The image is in the Public Domain. See Doyle (2016).

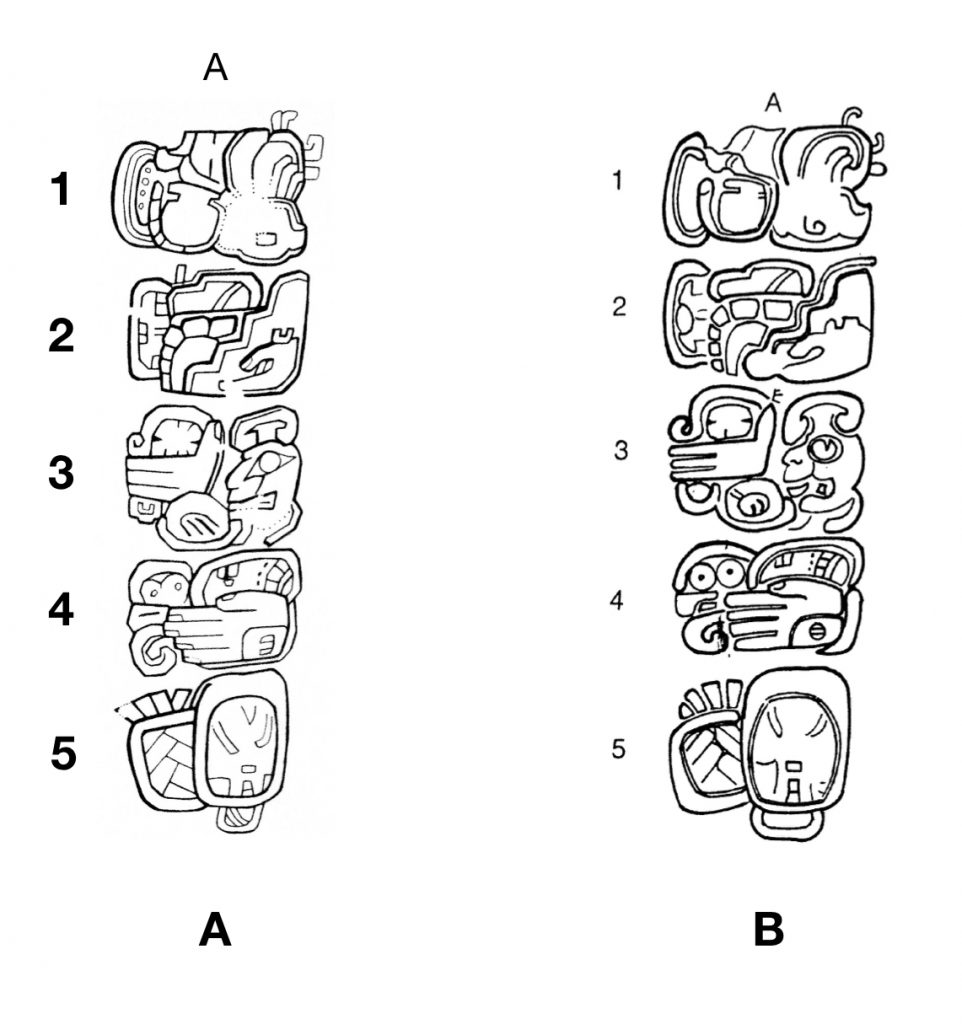

In 2003 I visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art in order to prepare a drawing of the text. I spent several hours, from opening until closing, examining the piece in person in order to prepare a drawing of the text. Prior to my visit, I scanned the photo of the text in Coe (1973:28) in high-resolution using Photoshop, inverted it to its negative image, and printed it out in enlarged format. Using tracing paper and pencil, and a portable light table, I then began to trace the major outlines of the glyph blocks and individual signs prior to my visit in order to capture the most obvious details and reserve the more challenging ones for my first-hand examination. Then, during my visit, I carefully traced the details of the inscription as I checked them against the carved text with adjustable raking light and magnifying lenses. Unfortunately I did not have at the time a camera capable of high-resolution close-up photographs. By closing time I had completed my pencil tracing and checked every detail, systematically, glyph block per glyph block, sign per sign. That said, I did not feel then that I had successfully captured every detail, as the text has experienced damage during its long history. For some aspects of glyph blocks A1 (signs A1d-e) and A3 (sign 3g), details are simply missing, obliterated; for other signs (sign A3d), details were unclear. I believe that I successfully gleaned a majority (maybe 60-70%) of the details of the text. A few days later I traced the pencil drawing with ink pens. My final rendering, available in Mora-Marín (2004:47, Fig. 3), is seen in Figure 2A, and may be compared to that published in Coe (1973:27) in Figure 2B.

Figure 2. Drawings in Mora-Marín (2004) and Coe (1973).

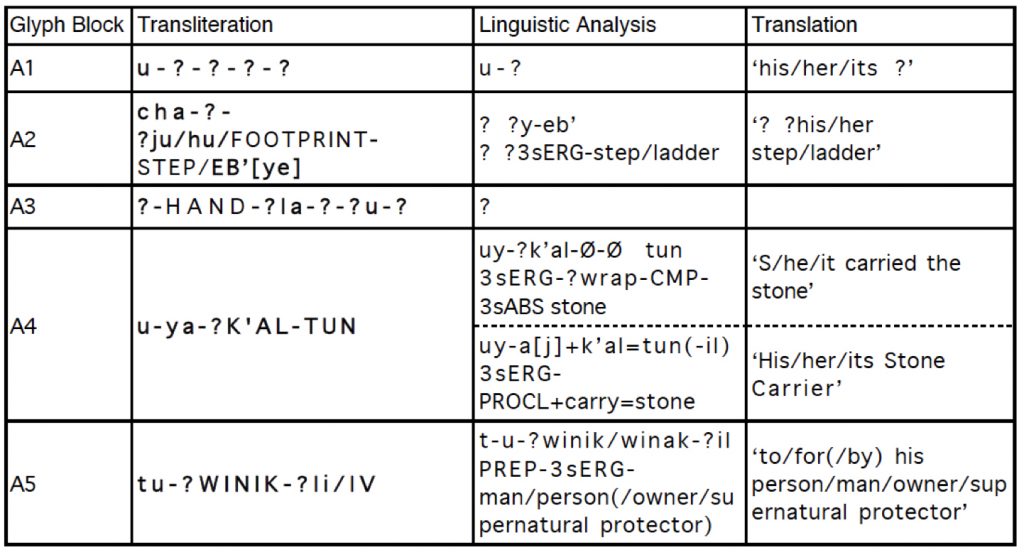

In Mora-Marín (2004:18-21) I made the drawing and also a description of the text available online through the FAMSI website. Table 1 reproduces the analytical sketch of the text I provided in that report. I will review the content of the text below, and in the process revise and update it.

Table 1

In my breakdown of the text I followed Coe’s (1973) formatting, A1-A5. I still stand by some of the identifications of individual signs (A1a, A2a, A2d, A3b, A3d, A4a, A4c, A4d, A5a, A5b, A5c) and one of the collocations (A5).

More recently, Houston (2011) has discussed this text in connection with the practice of “archaizing.” Interestingly, Houston has suggested that the vessel is Preclassic in form, and that the iconographic imagery is stylistically Preclassic as well, but argues that such style was the result of intentional archaization. Furthermore, he suggests that the associated text was stylistically later: “This is where interest mounts: against expectation, the glyphs appear to be fully Early Classic, not Preclassic, in date (n.b.: it is almost certain that the text and image are contemporary, in that the handle has the same relief as the images and could not have been added later).” He does not explain why the imagery would have been successfully archaicized while the text was not, but it is possible to imagine that two individuals were responsible for the work, one carving the imagery and the other the text. While light in justification, as no paleographic arguments are made explicit for the relative dating of the text and its alleged disjunction relative to the pictorial imagery, Houston’s blog introduces a high-resolution photograph of the inscription by Justin Kerr and a pencil sketch of the text prepared by Houston himself, both of which are linked here (https://decipherment.files.wordpress.com/2011/06/figure-4ab.jpg). His blog also offers remarks on the glyphic collocations that make up the text, reproduced here in its entirety:

Position A1 may contain a version of the TI’ logograph identified by David Stuart, and in a schematic form that is securely Early Classic. A sign for “mouth” accords with what was surely a drinking vessel, although it is unlikely to read “drink,” uk’, in this context because of the prefixed u pronoun. Just beneath it lies what may be a reference to the vessel itself, with body and neck somewhat visible. The probable t’abayi sign that composes part of A2 conforms to this dates [sic], as does what appears to be an admittedly aberrant spelling of a transitive verb at A4: u-K’AL-wa TUUN, doubtless in reference to the stone-bowl and its dedication. (The name of the god is, as mentioned before, at A2.) An unusual form of tu, a preposition with ergative pronoun, may figure in A5. To my knowledge, spellings of transitives come exclusively from the Classic period.

A careful examination of Justin Kerr’s high-resolution photo (Houston 2011:Fig. 4a) has led me to revise my thinking on some signs and elements. A3e is not adequately rendered in my drawing (or Houston’s): from Justin Kerr’s photograph, it is now clear to me that the sign is supposed to show an opened hand facing up and holding an object, and that what I had previously believed to be the last element or sign out of six on this glyph block, A3g, may actually be an extended finger connected to the hand sign in question, and so there are now only five signs in this glyph block. When considered in this light, this sign (A3d/g) is similar to one of the painted stucco medallion glyphs that formerly covered a gourd container (Vessel 17) recovered in Tomb 19 at Rio Azul (Adams and Robichaux 1992:Fig. 3–42), as seen in Figure 3, the difference being their orientation, with the sign at A3e on the spouted jar facing up, the one on the stucco medallion facing down. A future drawing will be needed to render these details more accurately.

Figure 3. Sign with open-hand holding object.

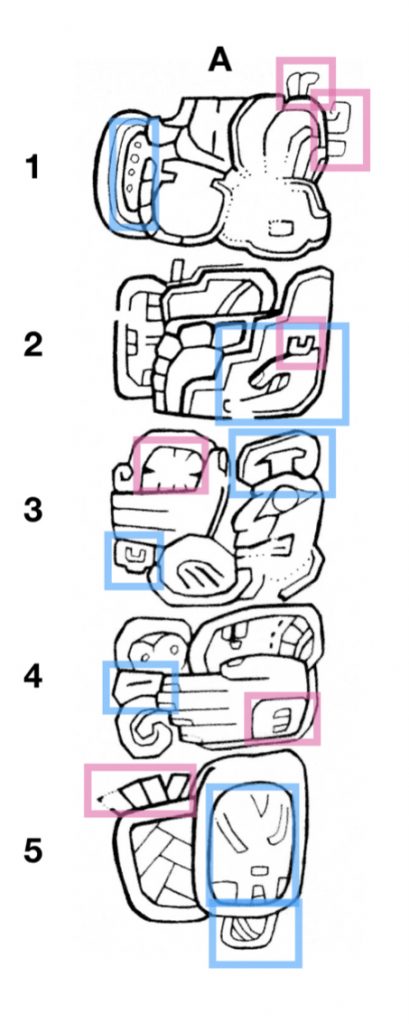

Houston’s (2011:Fig. 4b) drawing may be missing some minor details as well, some of which may not be significant for the purposes of reading signs, but others probably are so. I will review these from the top to the bottom. Figure 4 shows locations where I believe signs or sign elements are missing from Houston’s (2011) drawing that are either important for reading the whole text (contained within blue rectangles) or for stylistic or paleographic description of individual signs (contained within pink rectangles).

Figure 4

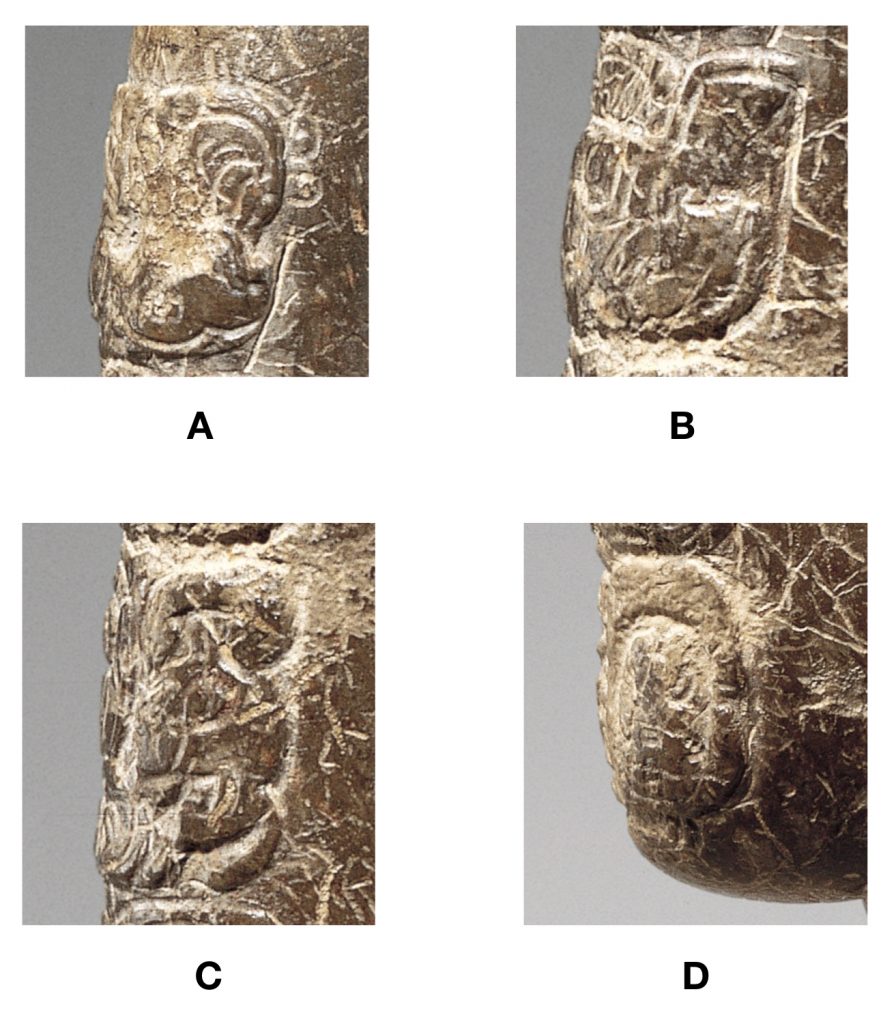

At A1a, Houston’s drawing is missing four dots that securely identify this sign as T1/HE6 7u.[2] Some of these dots are somewhat visible in Justin Kerr’s high-resolution photo (Houston 2011:Fig. 4a). Also missing, this time from A1d, is the “floral” ornamentation seen in Coe’s drawing and my own, and unambiguously visible in the photograph published in Fields and Reents-Budet (2005:188), as well as that in Doyle (2016), as seen in Figure 5A. These floral elements may have been added at a later time, perhaps even long after the initial carving of the text.

Figure 5

At A2a, Houston’s drawing is missing only minor elements, but elements that nonetheless point to the sign being the syllabogram T520/XS3 cha. At A2d, Houston’s drawing is missing an important sign which undoubtedly affects the reading of the glyphic collocation it is contained in, and perhaps the entire text: a hand-shaped sign that appears to correspond to the syllabogram T220ab/MZR ye. This sign also bears a characteristic U-shaped element seen with this particular sign in Late Preclassic and Early Classic texts. Both the photo by Justin Kerr employed by Houston (2011), as well as the available in Doyle (2016), a detail of which is seen in Figure 5B, support this identification. The sign was likely used in lieu of T17/ZUH yi, to partially spell the expected -V1y suffix of the STEP verb that precedes it.

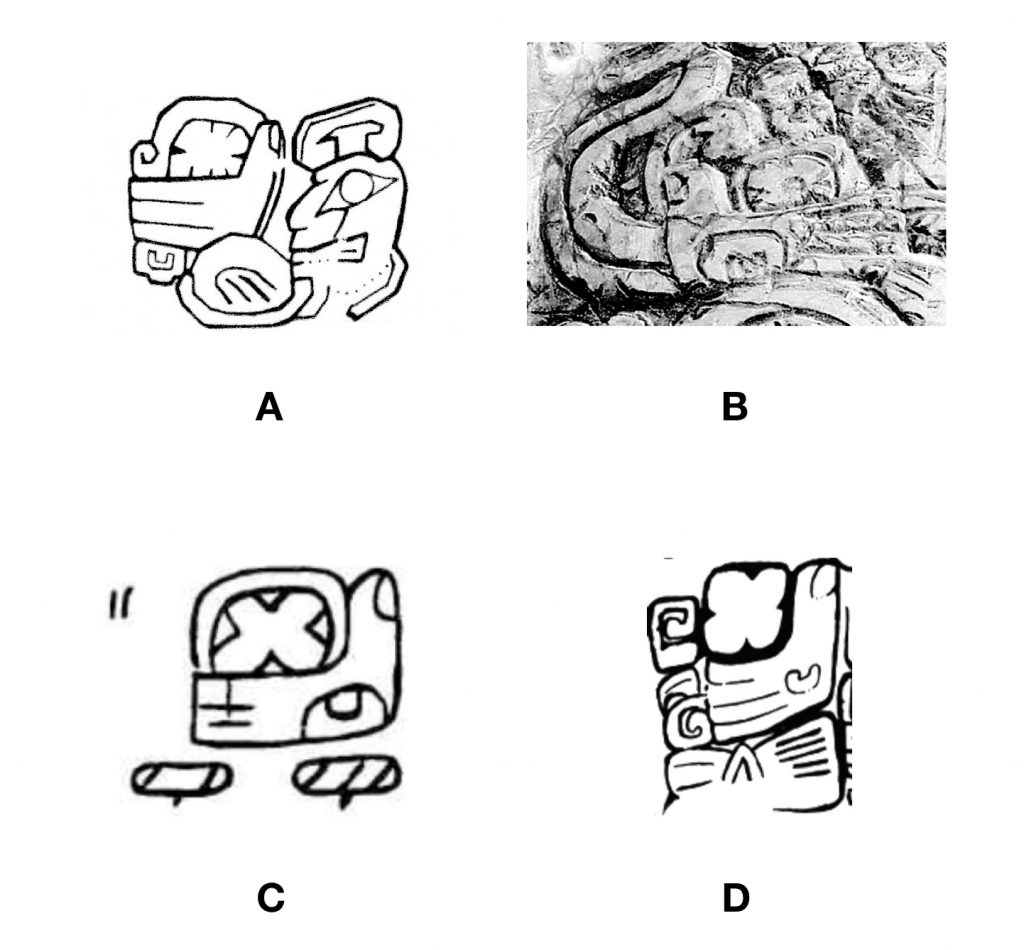

At A3a my drawing, seen in Figure 6A, may be showing more striations within the probable K’IN component of the “k’in-in-hand” sign than are supposed to be there, so that Houston’s drawing is likely more accurate. At A3b, Houston’s drawing does not render what appears to be a trefoil-shaped example of T178/AMB la, one that may contain a U-shaped element; his version is somewhat circular instead, with traces of a diagonal line inside. Such diagonal line is, in my opinion, a scratch —an example of damage to the text. The “k’in-in-hand” sign is also present in the pictorial imagery as an iconographically embedded glyph, Figure 6B. Commonly, the “k’in-in-hand” sign is accompanied by a la subfix, as in Figure 6C, which shows a glyph block from the trimmed jade belt plaque at Dumbarton Oaks (PC.B.586, http://museum.doaks.org/objects-1/info/22541), although in at least one instance, it bears a ma subfix in a glyph block from the San Diego Cliff Carving, seen in Figure 6D. At A3c, Houston’s drawing seems to leave out an important internal detail that renders this sign as a bracket that likely corresponds to a design of 7u without dots or central triangular element, which can be appreciated in Figure 5C. This sign likely spells u- ‘third person singular ergative/possessive’, and is therefore crucial to understanding the structure of the text. Lastly, as I have already noted, my 2003 drawing inaccurately renders the bottom components of this glyph block: it should show, at A3e, a sign shaped like an opened hand with a rounded object in it. Houston’s drawing is also missing this sign.

Figure 6

At A4b, there is a discrepancy between my drawing and Houston’s. My drawing renders A4b as an abbreviated version of T126/32M ya, showing only two elements instead of the usual three; similar abbreviations are common in the Classic period. Houston’s drawing renders it as a simplified version of T130/2S2 wa. Despite its unusual location, noted as such by Houston, wa would make more sense as far as reading the entire glyph block. At A4d, Houston’s drawing is missing another example of a U-shaped element contained within the logogram T713/MR2 K’AL (or CH’AL) for ‘to bind/wrap/adorn’, visible in my 2003 drawing, but also detectable in the photograph by Justin Kerr’s in Houston (2011:Fig. 4a). Such element does not affect the reading, but further supports an early dating of the inscription.

At A5a, my drawing differs from Houston’s mainly in the style of the top elements: mine renders them in an angular fashion, his in a curvilinear fashion. However, crucially, A5b in my drawing (and Coe’s) is rendered in a way that resembles T521/XS1 WINIK/WINAK, for winak/winik ‘man, person’, but Houston’s drawing merely shows three dots. The missing details are visible in the photos in Field sand Reents-Budet (2005), Doyle (2016), as seen in part in Figure 5D, and in the photograph by Justin Kerr in Houston (2011:Fig. 4a). Another important missing detail from Houston’s drawing is the last sign of the entire text: sign A5c. This sign resembles a Late Classic syllabogram T24/1M4 li, as suggested in Mora-Marín (2004:17, Table 1), but it may simply be a T617/1M3 MIRROR sign, argued in Mora-Marín (2012) to have a value WIN ‘eye/face’ (or syllabographic win) in some contexts. The sign appears below the glyph block itself, incised on the surface of the handle in a different plane as the raised relief of the glyph blocks. It was added after the carving of the glyph blocks themselves. It was rendered in Coe’s drawing, although lacking internal elements, and also in mine, showing two diagonal bands within a cartouche. If the sign in question is in fact the syllabogram li, it is possible that it may have been added at a time that postdates the initial carving of the text, a time when the hook-shaped version of the Late Preclassic and early Early Classic li had given way to a more oval-shaped version.

Now, a few remarks can be attempted with regard to the inscription. Glyph block A1 includes a total of five signs. It begins with a design of 7u at A1a. Sign A1b is incomplete and unclear as to what it depicts, much less what its value might be. Sign A1c depicts a vessel; as such it could be a reference to the spouted jar itself. It resembles a jar-shaped sign texts, YG2, employed in several instances as the day sign MULUK, but also as a syllabogram 7u in other contexts (e.g. 7u-tz’i-b’a for u-tz’ihb’-a-Ø ‘s/he wrote it’). Since the term for ‘drinking cup’ was 7uk’ib’(-aal), and since the day name corresponding to MULUK is typically associated with water in other Mesoamerican ritual calendars, it is possible that the syllabographic value 7u for YG2 was derived acrophonically from 7uk’ib’(-aal), and that such sign was used in the spelling of the day sign MULUK due to such association. If the jar-shaped sign at A1c on the spouted jar is an early version of YG2, perhaps it functioned logographically as 7UK’(IB’) in this context. Although Houston (2011) remarked, regarding this glyph block, that “A sign for “mouth” accords with what was surely a drinking vessel, although it is unlikely to read “drink,” uk’, in this context because of the prefixed u pronoun,” it must be recalled that Piedras Negras Panel 3 bears a spelling 7u-7UK’-ni for 7uk’-(V)n-i-Ø ‘he drank’, where we find a sign 7u precisely before the logographic spelling for ‘drink’. That said, since only one sign, A1a 7u, can be identified and read in this glyph block at this point, it is premature to speculate any further, except to suggest that it is possible that it spells the u-‘third person singular ergative/possessive’ marker, either preceding a noun or verb.

Table 2. Breakdown of the text with some suggested readings.

| Transcription | Transliteration | Grammatical Options | Paraphrase | |

| A1 | 7u-?-?-? | u-… | Possessed noun (or active transitive verb) | (it is) his/her X (or s/he Xed it) |

| A2 | ?cha-STEP[ye] | ?-V1y(-e…) | Inchoative verb | s/he/it became Xed |

| A3 | ?-?la-?7u-?-? | “k’in-in-hand” seems to represent a relationship term in other texts | Perhaps a noun or noun phrase (possibly including a relationship term) | Proper name? |

| A4 | 7u-?wa-K’AL-TUN | u-k’al-aw-Ø tuun | Active transitive verb | s/he bound/wrapped/adorned the stone (vessel) |

| A5 | tu-WINAK/WINIK-?win/?li | t-u-winak(-iil) | Preposition ta/tä ‘to/for’ followed by u- ‘his/her/it’ followed by winak/winik ‘man/person’ or winak/winik-iil‘owner’ | For his/her person/body/owner |

A2 appears to open with a version cha and to close with a version of ye. In between are two signs, one resembling a small platform with a vertical element on the step, the other resembling T843/ZY1, the STEP glyph, read by some epigraphers as T’AB’ (Stuart 1995, 1998, 2005; Wagner in Schele and Grube 1997:195), although the precise lexical and semantic identification is not always specified (there are at least two options, ‘to rise’ and ‘to annoint’). As I noted above, it is possible that the ye sign is in part providing the expected spelling of the -V1y suffix commonly seen with this expression, which I have argued serves to derive “ingressives” (Mora-Marín 2007), whether inchoatives (‘to become X’) or versives (‘to begin to become X’).

As already discussed, A3a bears an example of the so-called “k’in-in-hand” sign, which is typically preceded by ya, followed by la, and in one instance, on the San Diego Cliff carving, preceded by ya and followed by T74/32A ma. A3b may constitute an example of la. The following sign is, in my opinion, a design of T1 7u, followed by a sign that represents the head of an animal, showing a prominent eye, human or otherwise. At the bottom would be a sign shaped like an opened hand holding an object. I suspect this glyph block bears a proper name, as suggestion supported by the iconographically embedded example on the spouted jar (cf. Figure 6B), occurring atop the head of one of the depicted personages, as observed by Coe (1973:26), or a genealogical statement, but nothing more can be said with confidence at this time.

Mora-Marín (2004) I suggested that A4 presented an unusual spelling 7u-ya-K’AL-TUN , with uy- preceding k’al , even though uy- is the prevocalic allomorph that would normally precede roots beginning with /7/. Following Houston’s (2011) suggestion, a more straightforward reding would be 7u-wa-K’AL-TUN, where wa would still be present in an unusual position, as the more common, expected spelling would have been 7u-K’AL-wa-TUN. His reading supports a more straightforward active transitive inflection u-k’al-aw-Ø followed by tuun ‘stone’: ‘s/he bound/wrapped/adorned the stone’. As Houston suggests, ‘stone’ may refer the spouted jar itself.

The last glyph block, A5, may read t-u-winak/winik-iil. In both Ch’orti’ and Tzeltal the possessed and suffixed form of winik ‘man, person’ can refer to ‘owner’: Ch’orti’ u-win(i)k-ir ‘its owner’ (Hull 2016:324, 400, 487) and Tzeltal s-winik-il-el ‘its owner’ (Polian 2015:798). Perhaps the text refers to the ‘binding’ or ‘wrapping’ of the stone vessel ‘for its (intended) owner’, that is, prior to the actual gifting or presentation of the vessel to the intended owner.

To conclude, there remain too many uncertainties to attempt a reading of the whole text. Hopefully future findings of similar texts on similar artifacts will provide more parallels. It is very likely too that future attempts at documenting the inscription will improve on the currently available drawings.

Acknowledgments. My detailed examination and documentation of the Diker bowl in 2003 was only possible due to the generosity of Julie Jones and Amy Chen at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and support of FAMSI grant #02047 (Mora-Marín 2004). I am also grateful to James Doyle for sharing information on the spouted jar, including a 3D model prepared the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

[1] From this point forward I use grapheme codes by Thompson (1962), designed by an initial “T” followed by a numeral, as well as the grapheme codes by Macri and Looper (2003). Also, I will use <7> for [ʔ] out of typographical convenience.

[2] See Houston (2017) for a recent discussion of cacao-serving vessels, including the Diker bowl.

References

Adams, Richard E. W., and Hubert R. Robichaux. 1992. Tombs of Río Azul, Guatemala. Research and Exploration: A Scholarly Publication of the National Geographic Society 8:412-427.

Coe, Michael. 1973. The Maya Scribe and His World. New York: The Grolier Group.

Doyle, James. 2016. Spouted Jar. URL: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/318346?searchFie…sortBy=Relevance&ft=maya&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=16.

Fields, Virginia, and Dorie Reents-Budet. 2005. Lords of Creation: The Origins of Sacred Maya Kingship. London: Scala Publishers Limited.

Houston, Stephen. 2017. Forgetting Chocolate: Spouted Vessels, Coclé, and the Maya. Maya Decipherment Blog. URL: https://mayadecipherment.com/2017/09/24/forgetting-chocolate-spouted-vessels-cocle-and-the-maya/.

—–. 2011. Bending Time Among the Maya. Maya Decipherment Blog. URL: https://mayadecipherment.com/2011/06/24/bending-time-among-the-maya/.

Hull, Kerry. 2016. A Dictionary of Ch’orti’ Mayan-Spanish-English. Salt Lake City: The University of Utah Press.

Macri, Martha J., and Matthew G. Looper. 2003. The New Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs, Volume One, The Classic Period Inscriptions. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Mora-Marín, David F. 2004. The Primary Standard Sequence: Database Compilation, Grammatical Analysis, and Primary Documentation. FAMSI Report. URL: http://www.famsi.org/reports/02047/FinalReport02047.pdf.

—–. 2007. The Identification of an Ingressive Suffix in Classic Lowland Mayan Texts. In Proceedings of the CILLA III Conference, October 2007, Austin, Texas, edited by Nora England, pp 1-14. Austin: Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America, Linguistics Department, University of Texas.

—–. 2012. The Mesoamerican Jade Celt As ‘Eye, Face’, and the Logographic Value of Mayan 1M2/T121 as WIN ‘Eye, Face, Surface’. Wayeb Notes 40.

Polian, Gilles. 2015. Diccionario Multidialectal del tseltal. https://tseltaltokal.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Polian_Diccionario-multidialectal-del-tseltal-enero2015-2.pdf.

Schele, Linda, and Nikolai Grube. 1995. Notebook for the XIXth Maya Hieroglyphic Forum at Texas. Austin: The University of Texas.

Stuart, David S. 1995. A Study of Maya Inscriptions. Ph.D. Dissertation, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee.

—–. 1998. “The Fire Enters His House”: Architecture and Ritual in Classic Maya Texts. In Function and Meaning in Classic Maya Architecture, edited by Stephen D. Houston, pp. 373–425. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

—–. 2005 Sourcebook for the 29th Maya Hieroglyphic Forum. Austin: Art Department, University of Texas at Austin.

Thompson, Eric J. 1962. A Catalogue of Maya Hieroglyphics. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.