Una posible función del diacrítico de duplicación como abreviatura de colocaciones

David F. Mora-Marín

davidmm@unc.edu

University of North Carolina

Chapel Hill

6/12/2022

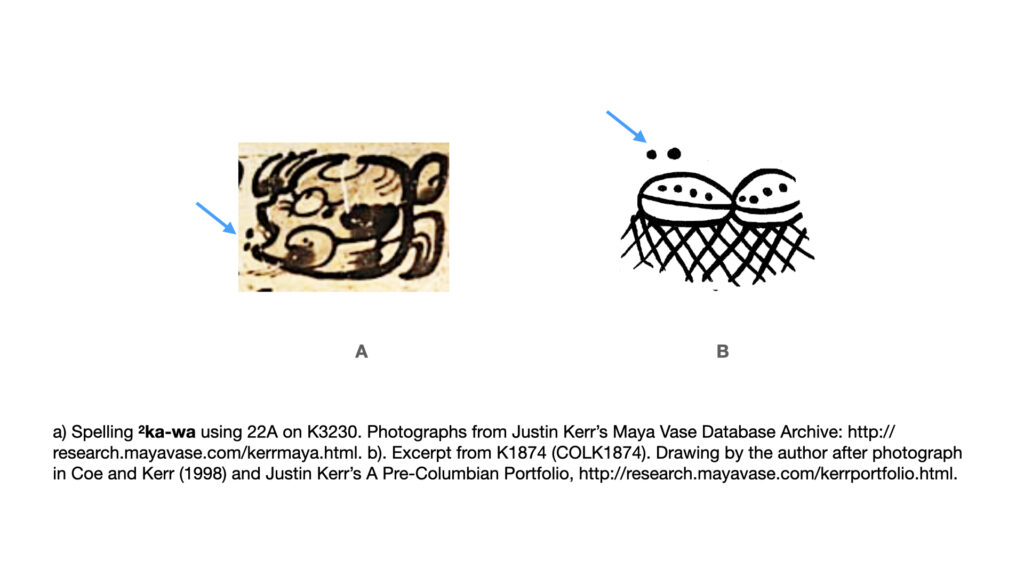

Esta nota trata sobre el diacrítico duplicador de la escritura maya (maya epigráfico), catalogada por Looper et al. (2022) como 22A, con al menos 133 ocurrencias en la Maya Hieroglyphic Database (Looper y Macri 1991-2022), en adelante MHD. Originalmente fue identificado y descrito por David Stuart en 1990 (Stuart 2014[1990]), quien definió su función básica como la de duplicar la lectura de un silabograma, como en las grafías muy comunes 2ka-wa, en lugar de ka-ka-wa, para käkäw ‘cacao’, o la grafía ocasional 2k’u, en lugar de k’u-k’u para k’uk’ ‘quetzal’, como se ve en la Figura 1.

Figure 1

Esta función está bien establecida y universalmente aceptada. De hecho, ha sido incorporada en las introducciones básicas a la escritura maya desde entonces (p.ej., Harris y Stearns 1992, 1997; Harris 1993, 1994; Kettunen y Helmke 2020). Las discusiones académicas más detalladas sobre el diacrítico son las de Stuart (2014[1990]), Stuart y Houston (1994) y, lo que es más importante, Zender (1999: 102-130). Aquí me concentraré en una sola pregunta, si 22A podría aplicarse a los logogramas, además de los silabogramas, y de ser así, con qué función.

Si bien Stuart (2014[1990]) y Stuart y Houston (1994) propusieron que 22A podía aplicarse a los logogramas, y que en tales casos su función era duplicar su lectura, al igual que para los silabogramas, los ejemplos a los que se referían esos autores eran en realidad casos de silabogramas, como ʔu y ʔa, empleados para representar morfemas gramaticales, tales como u- ‘tercera persona singular ergativo/posesivo’ y a- ‘segunda persona singular ergativo/posesivo’, respectivamente. Desde finales de la década de 1970 hasta principios de la de 1990, muchos autores suponían que dichos silabogramas funcionaban logográficamente cuando representaban morfemas gramaticales y, en tales casos, a menudo se transcribían en letras mayúsculas, al igual que los logogramas (p.ej., U- y A-). Sin embargo, desde un punto de vista puramente ortográfico, esto es innecesario: una simple estrategia de ortografía silabográfica es suficiente para explicar los usos de ʔu y ʔa cuando representan marcadores de concordancia de persona. De hecho, Zender (1999) concluyó que se aplicaba exclusivamente a los silabogramas. Aunque la noción de que los silabogramas podrían funcionar logográficamente para deletrear morfemas gramaticales fue posteriormente revivida como la Hipótesis de la Morfosílaba (Houston et al. 2001), una simple función de duplicación, el mismo tipo de función que se aplica a los silabogramas, es suficiente para explicar los casos en los que 22A es utilizado con silabogramas deletreando morfemas gramaticales. La única diferencia radica, en algunos casos, en si la acción de duplicación debe ser secuencial (p.ej., 2li para -(V)l-il ‘abstractivizador’ o 2le para -(V)l-el ‘abstractivizador’) o no secuencial (p.ej., 2ʔu-KAB’-CH’EN para u-kab’ u-ch’en ‘su tierra, su pozo/cueva’). Por lo tanto, definiría la duplicación secuencial y la duplicación no secuencial como subtipos de duplicación, pero ambos aplicables a los silabogramas.

Más recientemente, Kettunen y Helmke (2020) y Prager (2020) han sugerido que 22A podría colocarse en signos logográficos que representan raíces con formas C1VC1, como 2TZUTZ para tzutz ‘terminar’ (Stuart 2001; 2014[1990]) y 2K ‘AK’ por k’ahk’ ‘fuego’. 22A también se aplica a un signo catalogado por Looper et al. (2022) como ZRJ, parecido a una pelota. Kettunen y Helmke (2020:20) han defendido un valor K’IK’/CH’ICH’ para ZRJ, pero no presentan evidencia al respecto. Se puede suponer que esos autores estaban pensando en lenguas mayas en las que la palabra para ‘sangre’ también puede llevar la polisemia ‘(pelota de) caucho’. Uno puede citar la evidencia maya comparativa (Kaufman con Justeson 2003: 322–324) para pM *kik’ ‘sangre’, que en algunos idiomas mayas orientales (kaqchikel, poqomam, q’eqchi’, mam) y al menos un idioma maya occidental (Tuzantek) también puede tener el significado de ‘caucho’ además de ‘sangre’. Por lo tanto, los idiomas donde se atestigua la polisemia ‘sangre; caucho’ son idiomas mayas centrales. Prager (2020: 7), por su parte, presenta evidencia tentadora a favor de un valor KUK ‘paquete, textil; enrollar’ para ZRJ. Cualquiera que sea la lectura de ZRJ, el mejor análisis del uso de 22A con TZUTZ y K’AK’ es, de hecho, que los escribas lo usaban para marcar logogramas cuyas raíces tenían la forma C1VC1. Tal función de marcador de formas C1VC1, atestiguada en al menos 14 ejemplos en el MHD, probablemente se derivó analógicamente de la función original de 22A de duplicar silabogramas, dado que tal función siempre produce secuencias /C1VC1/ y se atestigua mucho antes que los primeros ejemplos de 22A con TZUTZ y K’AK’.

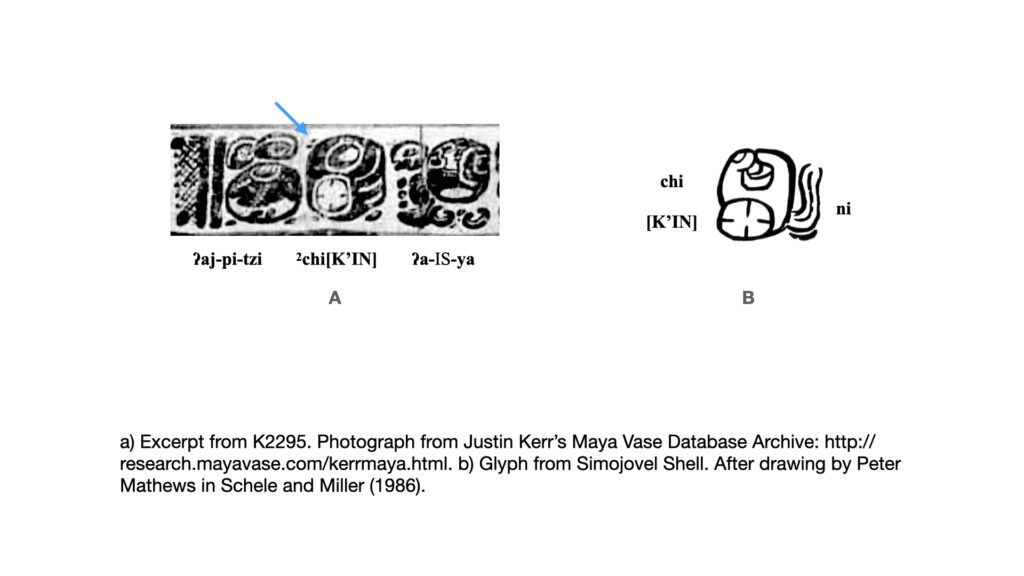

Hay otro tipo de situación, que no se ha discutido adecuadamente hasta el momento, en la que 22A parece aplicarse a logogramas. Sospecho que a este tipo de situación es a la que se referían Stuart y Houston (1994:46, pie de página 13) cuando afirmaron: “Todavía no entendemos por qué algunas grafías usan esta convención. Quizás señalen una ortografía particular cuando dos son posibles: chi-K’IN en lugar de K’IN-chi, o k’a-k’a en lugar de BUTS’, respectivamente”. Con respecto a K’AK’, ahora parece más probable que 22A se extendiera analógicamente para marcar opcionalmente logogramas con raíces con formas C1VC1, ya que no hay pruebas sólidas de un valor B’UTZ’ para b’utz’ ‘humo’ para este logograma . Con respecto al otro caso, desafortunadamente, Stuart y Houston no proporcionaron los ejemplos de chi-K’IN o K’IN-chi a los que se referían, pero es muy probable que uno de esos ejemplos, quizás el único ejemplo, se encuentre en K2295. En el texto de la Secuencia Estándar Primaria (SEP) presente en esta vasija, se encuentra la grafía 2chi[K’IN] (Figura 2A) al final del texto, inmediatamente antes de la Colocación del Signo Inicial que comienza el texto. Es probable que esto sea una ortografía de k’ihnich ‘radiante’. De hecho, la colocación 2chi[K’IN] está inmediatamente precedida por ʔaj-pi-tzi: la secuencia del título ʔaj-pi-tzi K’INICH está atestiguada en otros lugares, como la Escalera Sur de Uxul, Panel 03 (ver MHD, objabbr UXLSSP3), y fue uno de los títulos de K’inich Kan Bahlam II de Toniná. Esta grafía 2chi[K’IN] se puede considerar como una abreviatura: usando el MHD, se puede demostrar que existen más grafías logosilábicas de este término que incluyen T116 ni, o tanto T116 ni como T671 chi (Figura 2B), aproximadamente 120, que casos en los que se omitió T116 ni y solo está presente chi, con 17 casos. La abreviatura probablemente fue motivada por la ubicación de esta colocación al final del texto, donde no había más espacio. En consecuencia, parece que 22A funcionó en este caso como un dispositivo de puntuación, para indicar la abreviatura de una colocación, en este caso omitiendo un silabograma común (ni), de la misma manera que un punto también se usa para abreviar en los sistemas de escritura derivados del griego y el latín (por ejemplo, Dr., Prof., etc.).

Figure 2

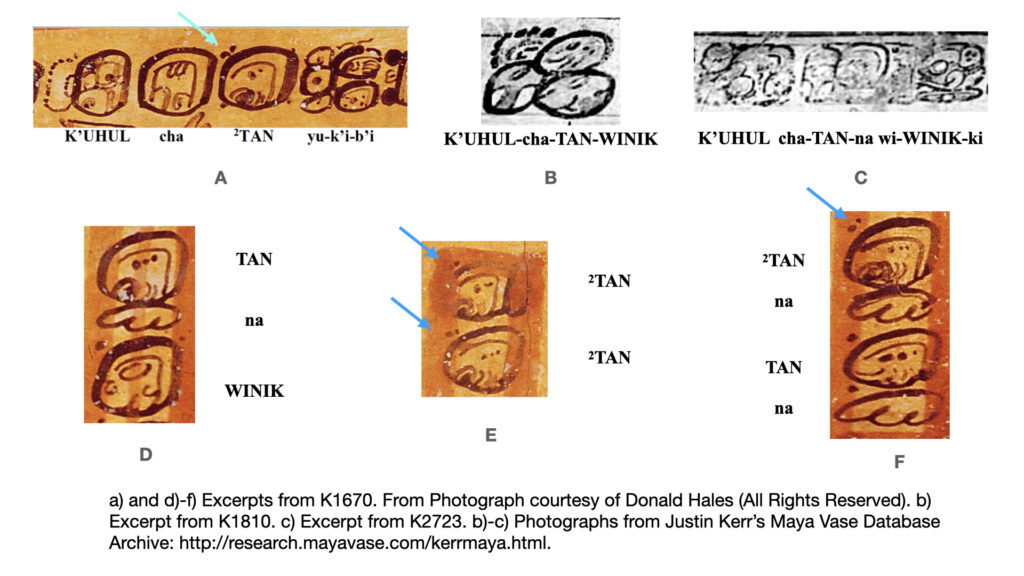

Otro ejemplo de esta función de abreviatura de 22A se puede encontrar en K1670. El texto SEP en esta vasija comienza con la colocación yu-k’i-b’i para y-uk’-ib’ ‘su copa’, y termina, como se ve en la Figura 3A, con una grafía del título común K’UHUL-cha-TAN-WINIK, parecida a las versiones compactadas y extendidas que se ven en las Figuras 3B-C. Este título, por supuesto, está vinculado a un sitio de ubicación desconocida, cuyo nombre a menudo se transcribe Chatahn, pero que se cree que se originó en la Cuenca Mirador (Boot 2005; Velásquez García y García Barrios 2018), y puede corresponder al sitio Preclásico de Tintal (Hansen et al. 2006). En K1670, el título aparece al final del texto SEP en el borde de la vasija como K’UHUL-cha-2TAN (Figura 3A), sin el característico logograma WINIK. Aquí, 22A se aplica al logograma TAN para tahn ‘pecho’, que es seguido inmediatamente por la expresión del vaso poseído que comienza el texto SEP. K1670 también contiene dos columnas glíficas. La estructura de estas columnas es difícil de evaluar, pero cada columna parece repetir parte de este título: una muestra TAN-na WINIK (Figura 3D), mientras que la otra muestra 2TAN 2TAN (Figura 3E) en la parte superior y 2TAN-na TAN-na (Figura 3F) en la parte inferior. A pesar de la estructura irregular de las dos columnas glíficas, el patrón se mantiene: cuando 22A está presente, WINIK está ausente, y cuando 22A está ausente, WINIK está presente. Una vez más, 22A se aplica a un logograma e indica que algo que normalmente está presente (otro logograma en este caso) ha sido omitido, por lo tanto, la colocación típica ha sido abreviada. En esencia, esto es lo que sucede cuando 22A indica la necesidad de duplicar la lectura de un silabograma: es una forma de señalar que falta algo, una interpretación adicional de un silabograma ya presente. La función de marcador de abreviaturas propuesta aquí, entonces, probablemente también fue una extensión analógica de la función básica de duplicación del diacrítico.

Figure 3

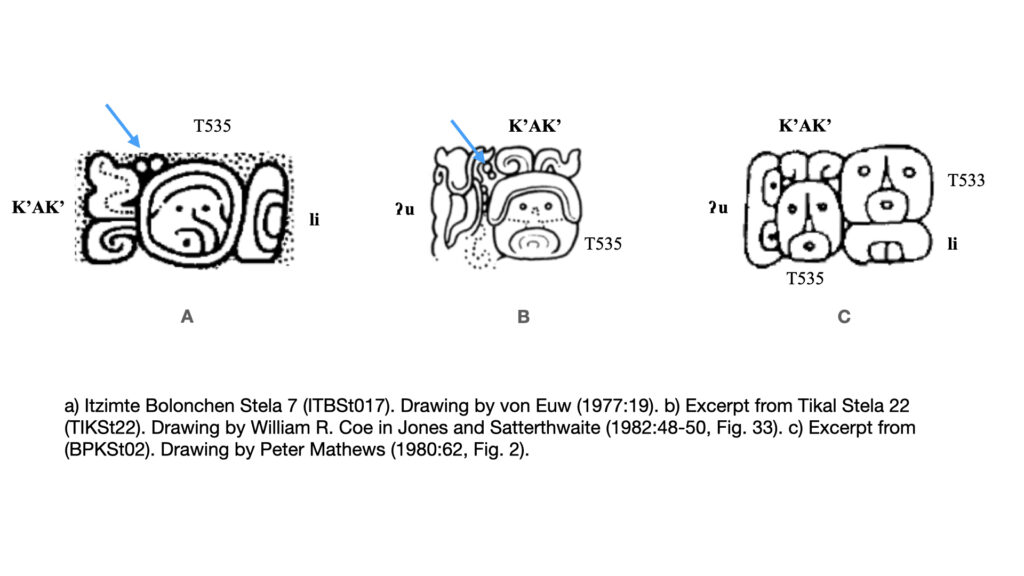

Hay dos ejemplos más que apoyan esta función de abreviatura. Éstos involucran la expresión de ‘hijo de padre’, y específicamente dos casos donde 22A se coloca entre K’AK’ para k’ahk’ ‘fuego’ y el signo T535 (Ajaw-con-casco), como se ve en las Figuras 4A-B. En esta colocación, T535/ZA3 (Ajaw-con-casco) y T533/ZA1 (Ajaw regular) pueden coexistir (Figura 4C). Cuando esto sucede, T535 siempre precede a T533. El diacrítico 22A solo aparece en dos casos, los dos ejemplos ya señalados, y en ambos casos es T533 el que aparentemente está ausente de la colocación. 22A no siempre aparece en los casos en que T533 está ausente; como ya se ha explicado, 22A es opcional. Pero los dos casos en los que aparece son casos en los que se ha omitido T533. En principio, se podría argumentar que ejemplos como los de las Figuras 4A-B (y ejemplos similares que carecen del 22A opcional) son instancias en las que T533, Ajaw regular, ha sido infijo dentro de T535, Ajaw-con-casco, lo que da la apariencia de que solo el Ajaw-con-casco está presente. Por lo tanto, 22A podría estar funcionando, en la rara ocasión en que está presente en la colocación del ‘hijo del padre’, para indicar que falta algo, específicamente, T533, o al menos que T533 no es obvio (dado que es idéntico a parte del signo T535).

Figure 4

Para concluir, 22A, el diacrítico de duplicación, puede funcionar para indicar que se ha abreviado una colocación y, por lo tanto, serviría como un signo de puntuación. El componente que falta puede ser un logograma o silabograma generalmente presente en tal colocación. Así, en tales casos, 22A parece funcionar a nivel supra-grafémico, a nivel de la colocación, más que a nivel grafémico, específicamente, en cuyo caso se aplicaría a un logograma o silabograma (como en su función duplicativa). Esta función de 22A se añadiría a las ya discutidas, resultando en una clasificación funcional de cuatro tipos: duplicación secuencial, duplicación no secuencial, marcador de forma C1VC1 y finalmente, marcador de abreviatura. Y es probable que todas las funciones estén relacionadas: se puede argumentar que la función de duplicación secuencial es la base, a través de diferentes tipos de reanálisis, para las otras tres funciones.

Referencias

Hansen, Richard D., Beatriz Balcárcel, Edgar Suyuc, Héctor E. Mejía, Enrique Hernández, Gendry Valle, Stanley P. Guenter, and Shannon Novak. 2006. Investigaciones arqueológicas en el sitio Tintal, Petén. In XIX Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2005, edited by Juan Pedro Laporte, Bárbara Arroyo y Héctor Mejía, pp.739-751. Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala. http://www.asociaciontikal.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/68_-_Hansen_et_al_-_2.05_-_Digital.pdf.

Harris, John F. 1993. New and Recent Maya Hieroglyphic Readings: A Supplement to Understanding Maya Inscriptions.

—–. 1994. A resource bibliography for the decipherment of Maya hieroglyphs and new Maya hieroglyph readings. Philadelphia: University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania.

Harris, John F., and Stephen K. Stearns. 1992. Understanding Maya inscriptions: a hieroglyph handbook. Philadelphia: University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania.

—–. 1997. Understanding Maya inscriptions: a hieroglyph handbook. Philadelphia: University Museum Publications, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Revised edition.

Jones, Christopher, and Linton Satterthwaite. 1982. The Monuments and Inscriptions of Tikal: The Carved Monuments. Tikal Report 33, University Museum Monograph 44. Philadelphia: University Museum, University of Pennsylvania.

Kaufman, Terrence, and William Norman. 1984. An outline of Proto-Cholan phonology, morphology, and vocabulary. In Phoneticism in Maya Hieroglyphic Writing, edited by John S. Justeson and Lyle Campbell, pp. 77-166. Institute for Mesoamerican Studies Publication No. 9. Albany: State University of New York.

Kaufman, Terrence, with John Justeson. 2003. Preliminary Mayan Etymological Dictionary. http://www.famsi.org/reports/01051/index.html.

Kettunen, Harri, and Christophe Helmke. 2020. Introduction to Maya Hieroglyphs. Seventeenth Revised Edition. Wayeb.

Looper, Matthew G., and Martha J. Macri. 2011-2022. Maya Hieroglyphic Database. Department of Art and Art History, California State University, Chico. URL: https://www.mayadatabase.org.

Looper, Matthew G., Martha J. Macri, Yuriy Polyukhovych, and Gabrielle Vail. 2022. MHD Reference Materials 1: Preliminary Revised Glyph Catalog. Glyph Dwellers Report 71.

Macri, Martha J., and Matthew Looper. 2003. The New Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs. Volume One: The Classic Period Inscriptions. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Macri, Martha J., and Gabrielle Vail. 2009. The New Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs. Volume Two: The Codical Texts. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Mathews, Peter. 1980. Notes on the Dynastic Sequence of Bonampak, Part I. In Third Palenque Round Table, 1978, pt. 2, Robertson, Merle Green, ed. Pp. 60-73. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Prager, Christian M. 2020. The Sign 576 as a Logograph for KUK, a Type of Bundle. Textdatenbank und Wörterbuch des Klassischen Maya, Research Note 15. https://mayawoerterbuch.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/twkm_note_015.pdf.

Stuart, David. 2001. A Reading of the “Completion Hand” as TZUTZ. Research Reports on Ancient Maya Writing, No. 49. Center for Maya Research, Washington, D.C.

—–. 2014. “Hieroglyphic Miscellany” from 1990. Maya Decipherment Blog. https://mayadecipherment.com/2014/02/25/hieroglyphic-miscellany-from-1990/.

Stuart, David, and Stephen Houston. 1994. Classic Maya Place Names. Studies in Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology 33. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

von Euw, Eric. 1977. Itzimte, Pixoy, Tzum. Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions 4.1. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University.

Zender, Marc U. 1999. Diacritical marks and underspelling in the Classic Maya script: Implications for decipherment. Unpublished M.A. thesis, Department of Archaeology, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada.