Mayan T757/AP9, the “Gopher” Sign, and Its Iconographic Counterpart in Epi-Olmec/Isthmian Writing

David F. Mora-Marín

davidmm@unc.edu

University of North Carolina

Chapel Hill

7/11/20

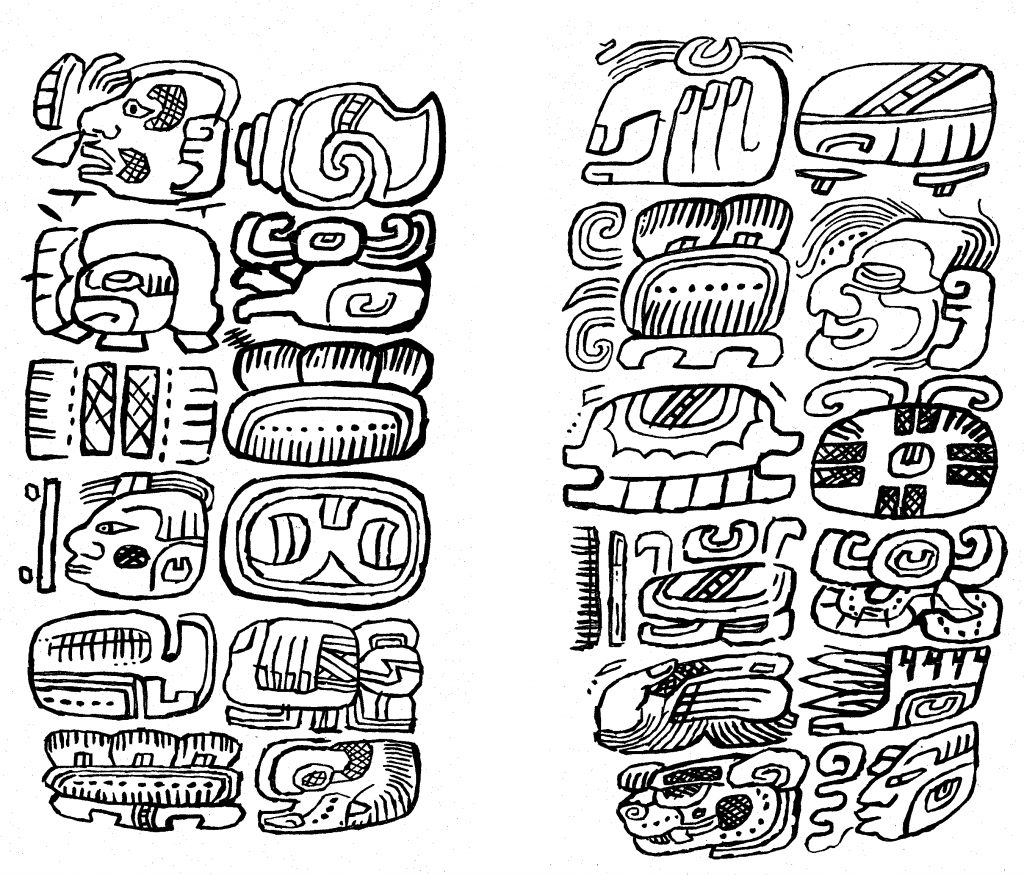

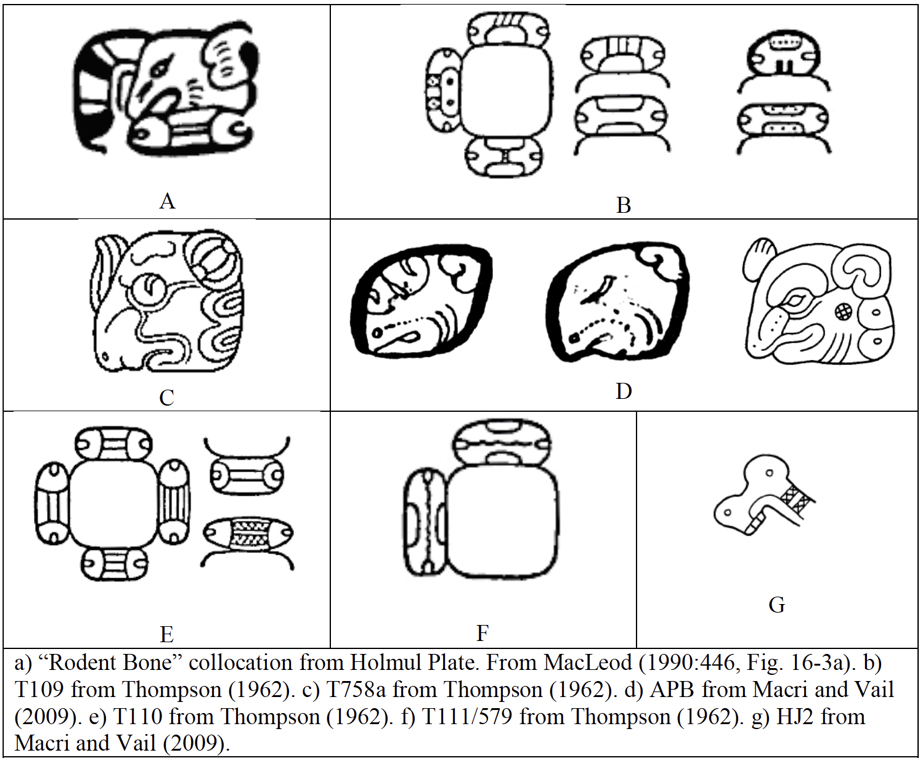

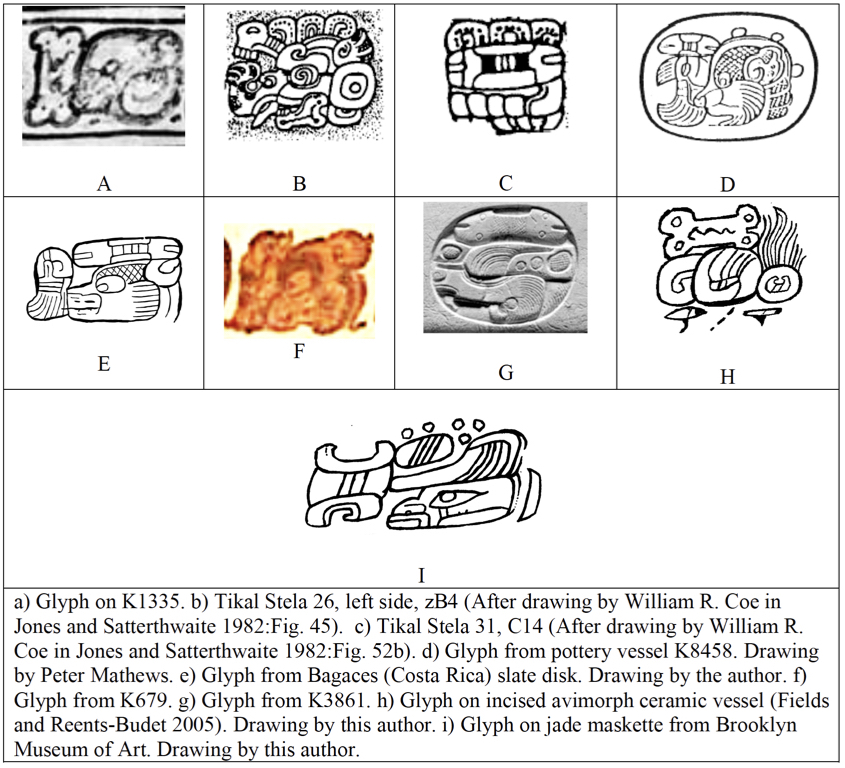

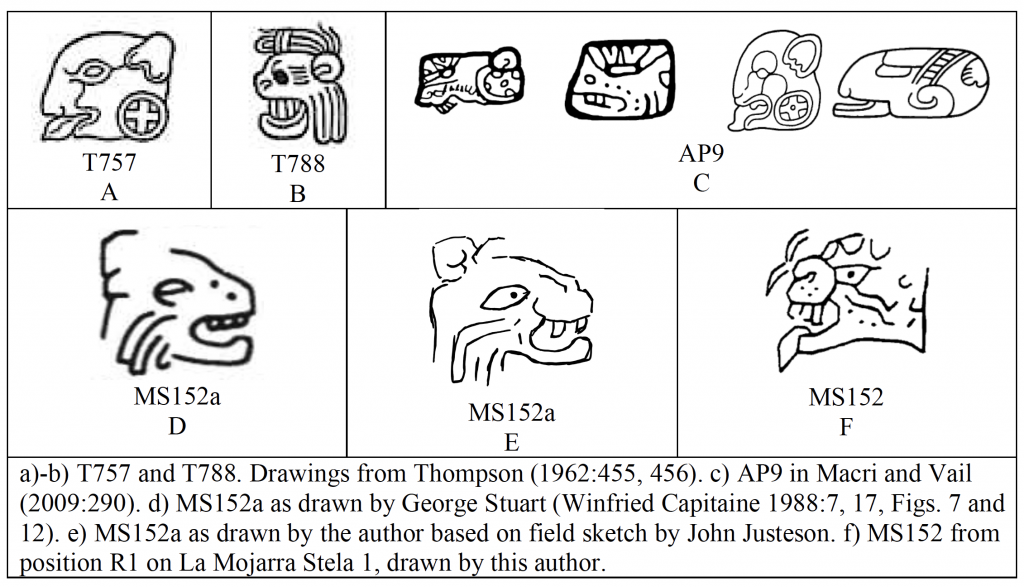

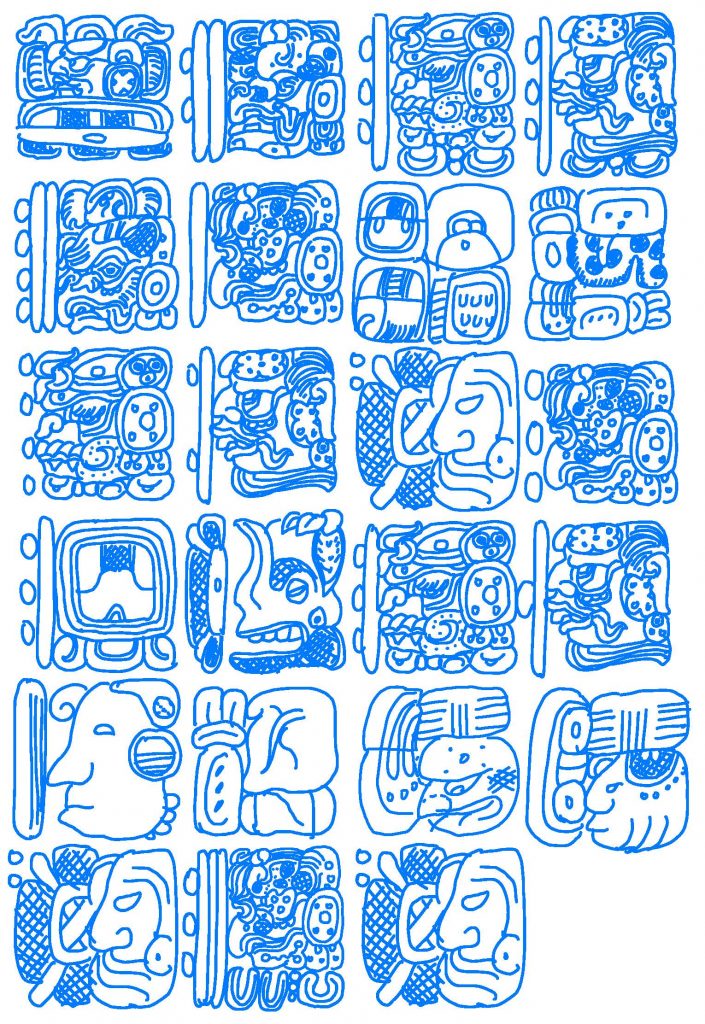

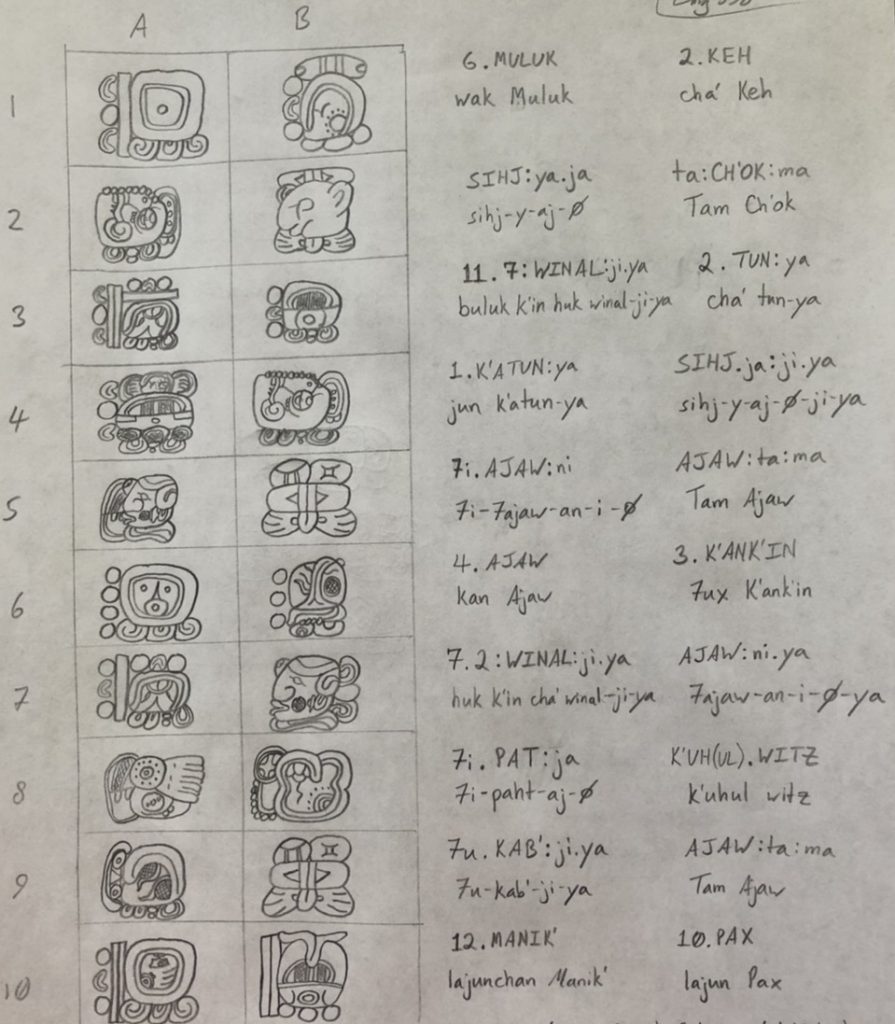

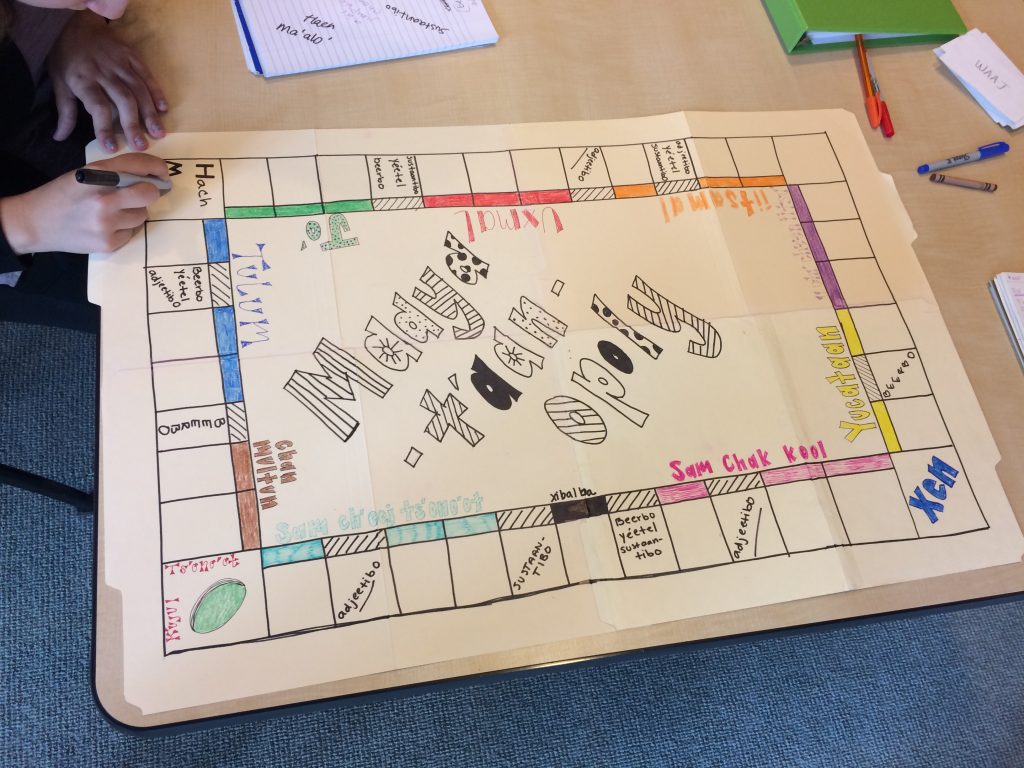

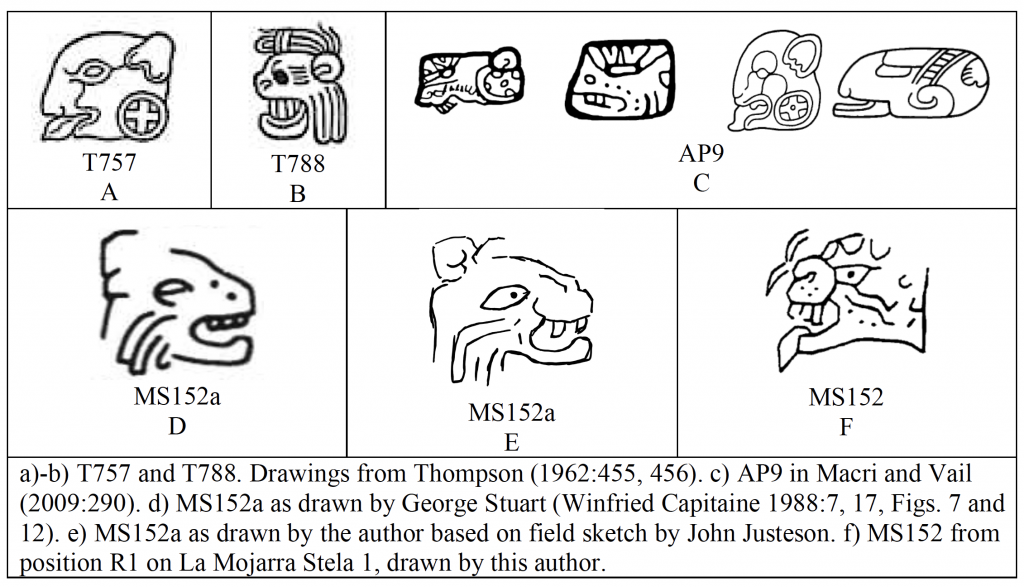

This note aims to show that Mayan T757/AP9 has an iconographic counterpart in Epi-Olmec/Isthmian writing, namely, MS152a: they both depict the head of a gopher. The Mayan version was designated with two codes in Thompson’s (1962) catalog, T757 (Figure 1A) and T788 (Figure 1B), the former corresponding to the Late Classic design, the latter to an Early Classic version—one that incorporates two signs, it would seem, T757 and T60. Macri and Looper (2003) and Macri and Vail (2009) have classified both versions, as well as the codical, Postclassic version, as AP9 (Figure 1C). It is noteworthy that T757/AP9 is often characterized by a T281 graphic infix behind the jaw, corresponding to logographic K’AN for k’an ‘yellow’, which does not contribute to the sign’s reading, but appears to be merely ornamental; similarly, the Postclassic version bears a T841 graphic infix on the forehead, corresponding to logographic 7AK’AB’ for 7ahk’ab’‘night, darkness’, but appears to be merely ornamental also. I return to these “ornamental” additions below. The Isthmian sign, so far a unique example found at position B3 on La Mojarra Stela 1 (Figure 1D), was not originally drawn in full detail by George Stuart (Winfield Capitaine 1988:7, 17, Figs. 7 and 12), and was rendered in a manner that made it too similar to the JAGUAR signs that occur elsewhere on the same monument (cf. R1, R14, T14); as a result, Macri and Stark (1993) and more recently Macri (2017) have classified the sign in question among the JAGUAR signs, cataloged as MS152. Among these, it corresponds specifically to the first example in the series, hence my classification as MS152a. The more recent documentation by John Justeson (Figure 1E) makes it clear that it is in fact a different sign: for one, it does not bear spots, like the JAGUAR signs (Figure 1F), it shows two teeth instead of three, and it lacks a tongue, unlike the three JAGUAR signs. They are otherwise similar, and in fact, the same may be said of some instances of Mayan T757AP9, and the Mayan sign for Jaguar, T751/AT1: in the past, some authors have identified T757/AP9 as a “jaguar” sign as well, not to mention also a kinkajou and a rabbit (cf. Macri and Looper 2003:75-76). As this note reviews, data adduced by a variety of authors, especially Bricker (1986) and Grube and Nahm (1994), points to a yellow pocket gopher as the iconographic referent of the sign.

Figure 1

Although the values of these respective signs are not the subject of this note, I begin with a brief overview of what is known. Mayan T757 it has long been established to be read as a syllabogram b’a, as in the spelling of /b’a/ or /b’ä/ sequences, e.g. 7u-tz’i-b’a for u-tz’ihb’-ä ‘s/he wrote it’ (i.e. -ä < *-a ‘factive’). It is most frequently used in the spelling of /b’ah/ phonetic sequences, either as a symbolic logogram B’AH or CVC syllabogram b’ah, to spell reflexes of Proto-Mayan *b’ah with cognates exhibiting polysemies involving ‘head, top, first, image’, and Proto-Mayan *b’aah ‘reflexive pronoun’, two terms that are likely etymologically related, as a variety of authors have attested (Bricker 1986; Schele 1990; Houston and Stuart 1998).[i] Such uses have been motivated by assuming an acrophonic origin in a reflex of Proto-Mayan *b’a7h ‘gopher’, which would have become *b’aah in Proto-Ch’olan-Tzeltalan and possibly endured as such in Pre-Ch’olan, prior to the Proto-Ch’olan merger of *VV, *V > *V.[ii] As Bricker explained, the value of T757, with its graphically infixed T281 (logographic K’AN for k’an ‘yellow’), as b’a and B’AH/b’ah, can be explained by lexical data from Tzeltal collected by Hunn (1977:206), who documents the terms 7ihk’al b’a ‘black pocket gopher’, tzahal b’a ‘red pocket gopher’, and k’anal b’a ‘yellow pocket gopher’. Bricker suggest that the commonly infixed K’AN logogram points to the last type, the yellow pocket gopher, as the species that is represented in the glyphic sign. Given this use of T281 K’AN to categorize the entity depicted by T757, Mora-Marín (2008:201, Fig. 4) has suggested that it functions as a semantic classifier, akin to those identified by Hopkins (1994) and Hopkins and Josserand (1999): signs that are not read aloud, but simply function to categorize the (emically salient) semantic field to which the depicted entity belongs, regardless of the sign’s orthographic function (i.e. logographic or syllabographic) or linguistic referent. T281 classifies the gopher depicted by T757 as, specifically, k’anal b’a ‘yellow pocket gopher’.

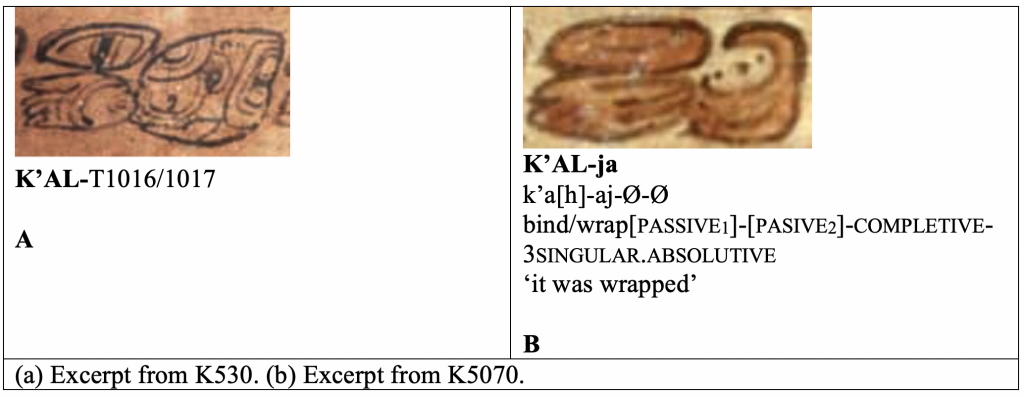

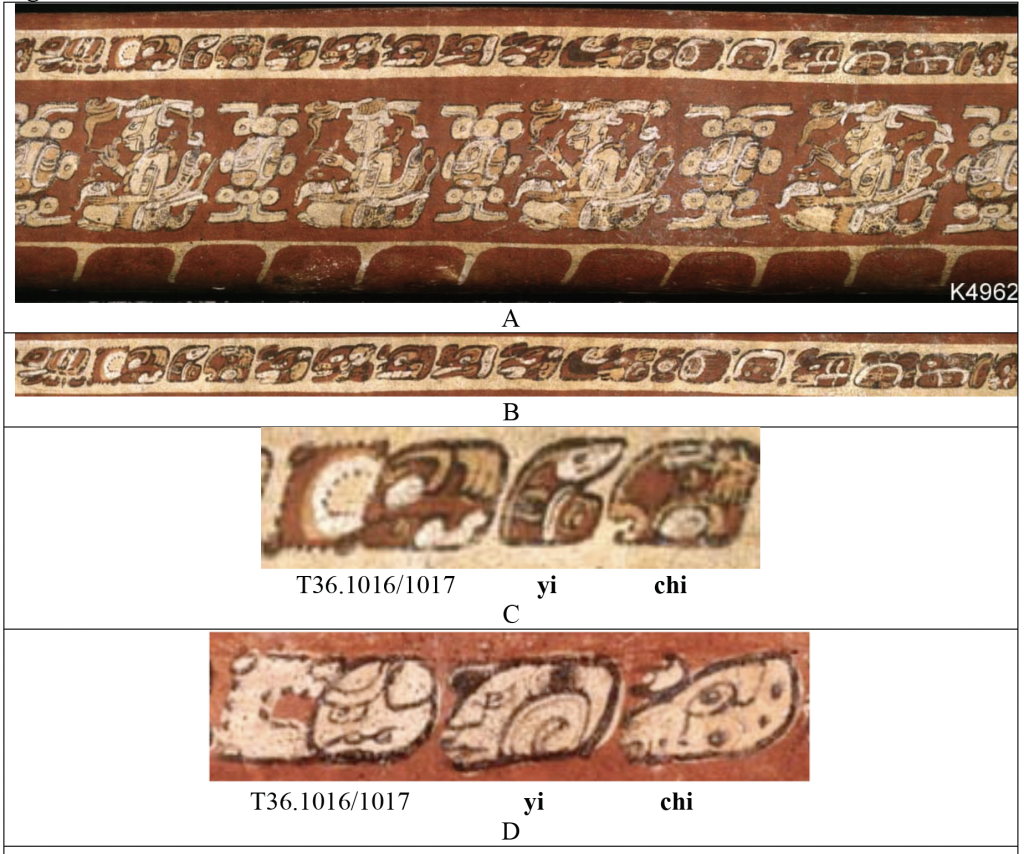

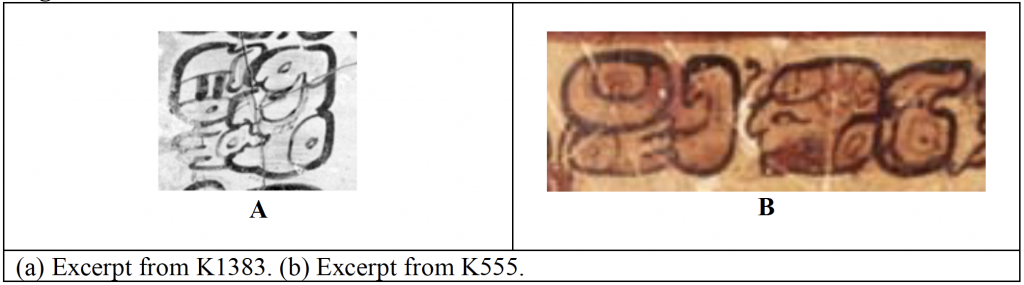

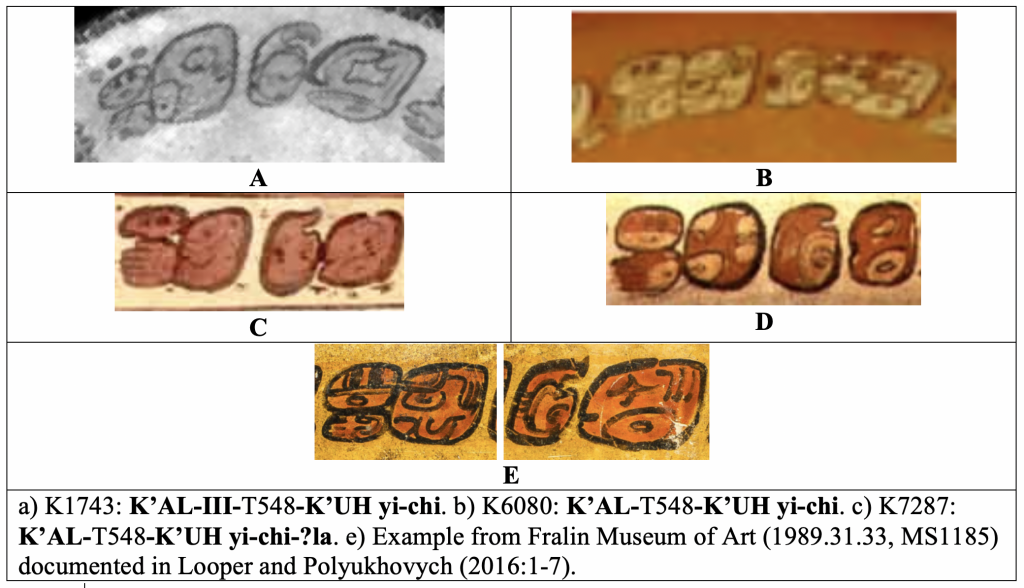

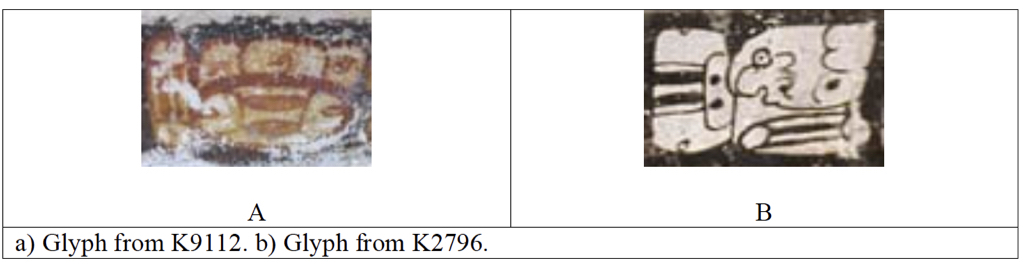

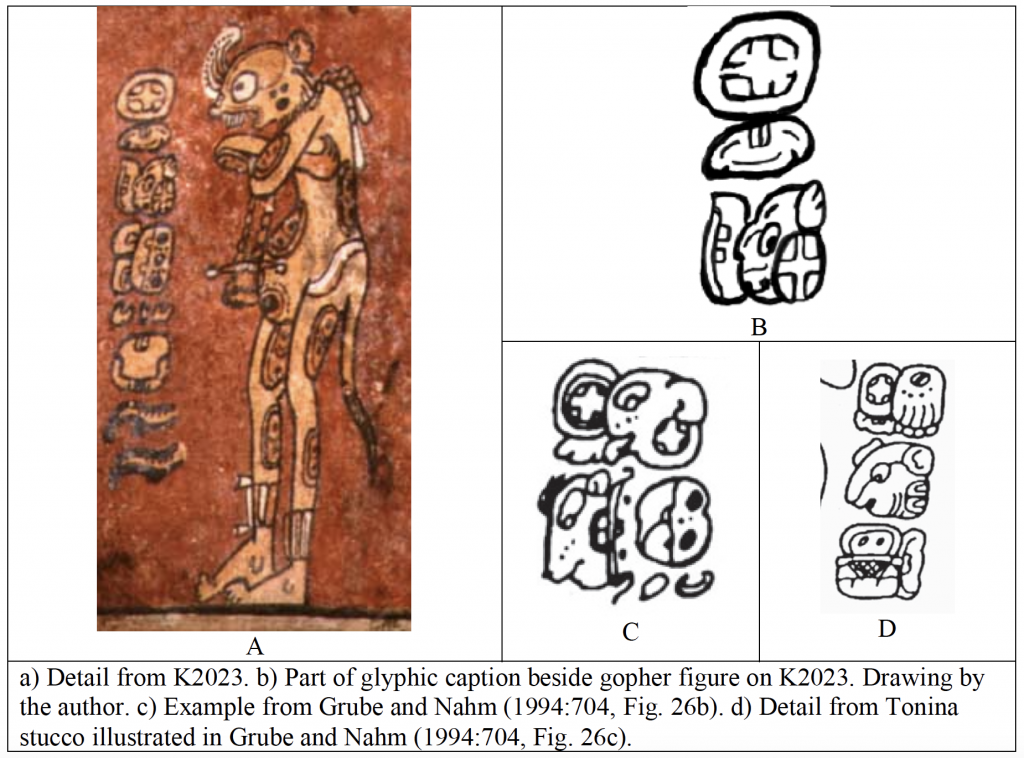

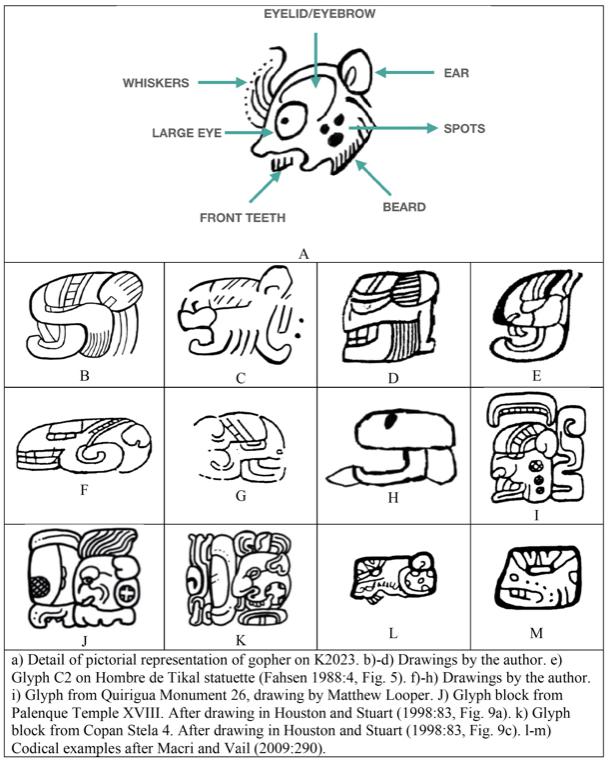

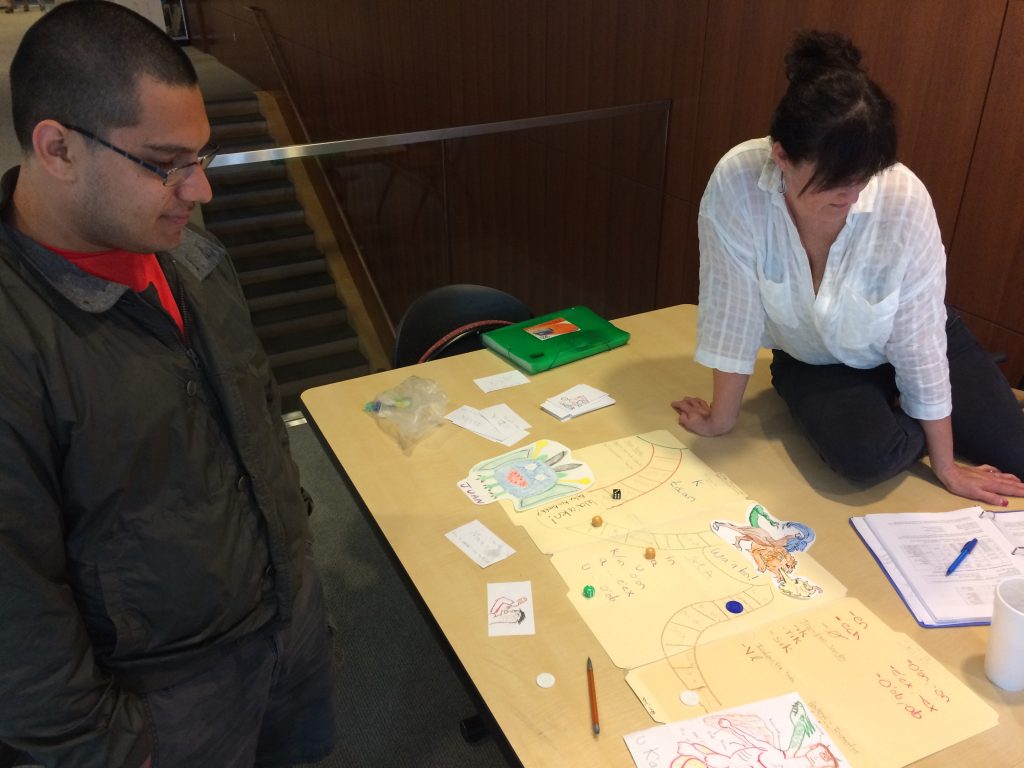

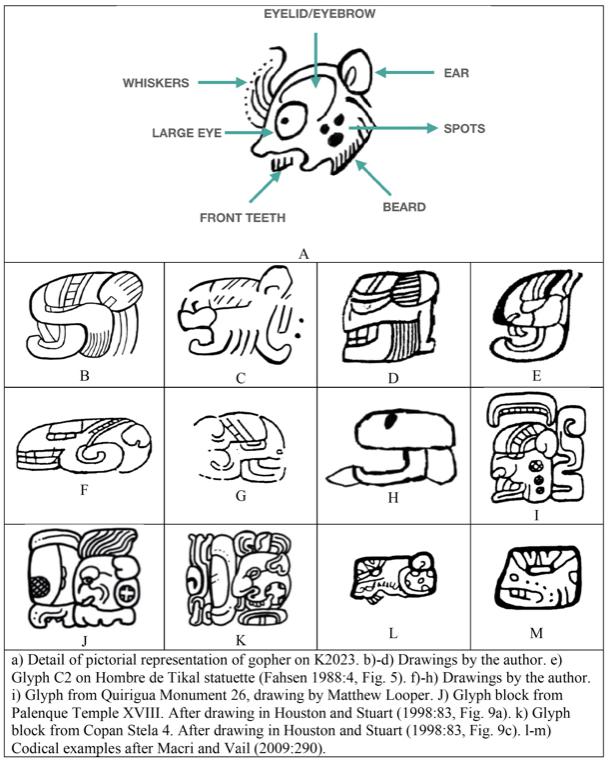

The question remained, for some time, whether a logographic value B’AH for b’a7h > b’aah > b’ah ‘gopher’ was actually attested in texts (Justeson 1989:33). The answer now seems to be affirmative. Grube and Nahm (1994:704) documented six instances of references to the yellow pocket gopher in Mayan texts, at least some of which seem to be references to wahy ‘co-essences; shapeshifters’. The example in Figure 2A, from vase K2023, is particularly interesting, as it provides a full-figure pictorial representation of a gopher beside a glyphic caption. Mora-Marín (2008:201, Fig. 4) also describes one of these instances, attested on vessel K2023, in detail, although he erroneously rendered one of the markings on the back of the depicted gopher on as an example of T281.) The glyphic caption (Figure 2B) spells K’AN-na B’AH for k’anal b’ah ‘yellow pocket gopher’. Grube and Nahm (1994:704) provide examples of two spellings of the same wahy that show a substitutional relationship between T757 b’ah/B’AH/b’a and T501 b’a in the spellings K’AN-na-b’ah/B’AH (Figure 2C) and K’AN-na-b’a (Figure 2D). These further support the identification with the yellow pocket gopher. In these last two examples the term for ‘yellow pocket gopher’ is followed by ch’o/CH’OHOK for ch’ohok ‘rat, mouse’, suggesting that scribes were classifying the gophers generally as ‘rodents’, with ch’ohok thus constituting the generic term, and k’anal b’ah the specific term.

Figure 2

As for Isthmian MS152a, Justeson and Kaufman (1993, 1997) and more recently Kaufman and Justeson (2001, 2004) have analyzed the passage that contains the one instance of this sign as referring to an eclipse. Specifically, they argue that the passage beginning at B1 and ending at B4, containing MS152a at B3, refers to a solar eclipse, an interpretation supported by the astronomical events associated with the chronological framework of the inscription; such an event would have been expressed linguistically as a “sun-eat(ing)-moon” phrase. The authors analyze the sign at B2 as a logogram for ‘sun’ and the sign at B4 as a logogram for ‘moon’, with MS152a in the middle, at B3, remaining as the only viable way of expressing ‘eat(ing)’; Kaufman and Justeson thus propose that MS152a functions as a logogram for ‘eat(ing)’.

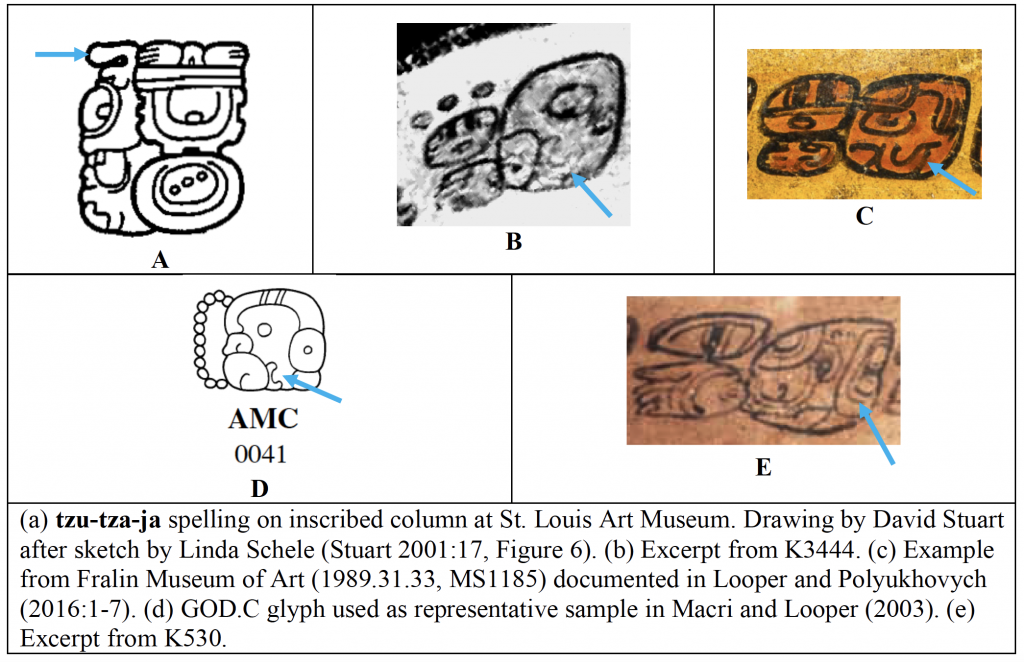

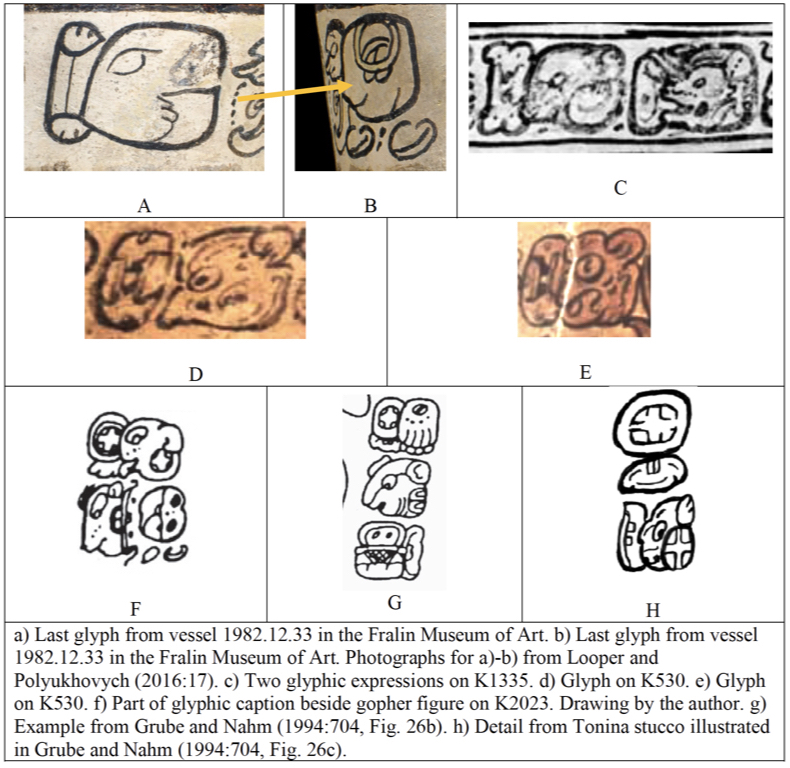

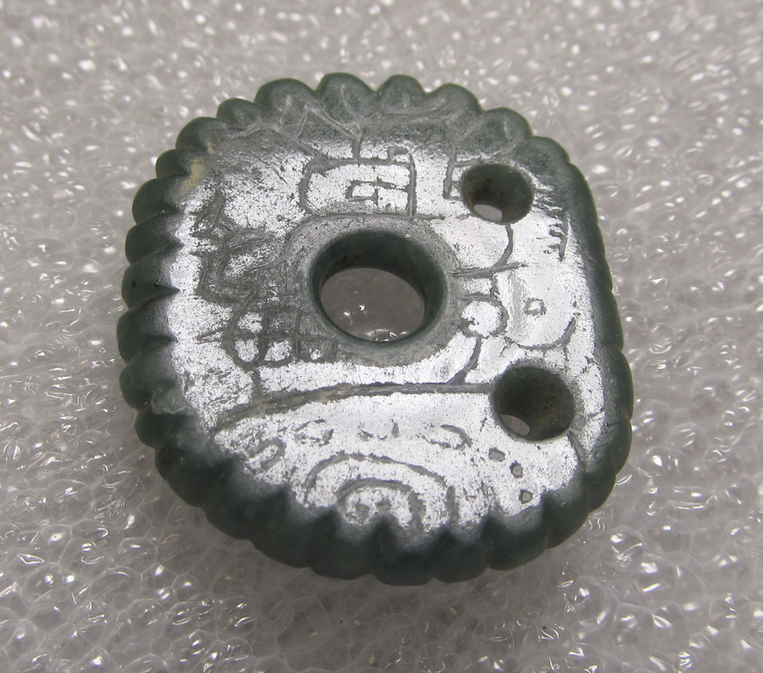

It is now time to compare the two, Mayan T757/AP9 and Isthmian MS152a. The comparison is merely iconographic: the argument made is that they pictorially depict the same zoological referent, a pocket gopher, and no argument is made that they function orthographically in a similar way. First, the iconography of Mayan T757/AP9 is described. As seen in Figure 3A, the pictorial depiction of the pocket gopher on K2023, the gopher’s head is rendered with prominent upper front teeth. The whiskers are rendered seemingly like a tuft of hairs/fur because the artist is only showing the whiskers on the opposite side of the profile head, to avoid overcrowding the side of the head that is depicted. There is a beard-like component (think lambchops), simply a way of representing prominent fur on the side of the head. The ear is prominently portrayed. There are spots as well, a trio of them. And the eye is shown as rather large. The T757/AP9 sign shows a great deal of variation in terms of the rendering of some of these components, plus additional elements not included in the pictorial version. I describe first a few early examples. Figure 3B shows an example from an inscribed slate disk from the area of Bagaces, Costa Rica: it shows prominent lower front teeth, the eye, the ear, and the chops. It also bears a vertical band toward the back of the head, and a “mirror” (T617) sign inserted in the space above its eye. And as is typical of the Early Classic instances of this sign, a very large, somewhat (even hook-shaped) curved jaw. Mora-Marín (2012) has argued this MIRROR sign to read WIN ‘eye, face’, and remarks on its common, preposed to or infixed into or conflated with T757/AP9 in the ‘it is the image/portrait of’ expression. The example in Figure 3C is found on the Hatzcap Ceel diorite axe (Mora-Marín 2018), also as a reference to an ‘image’, or as that author argues more specifically, as a reference to a ritual statuette or figurine. It bears the large, curved jawbone mentioned before, the beard-like or chops-like component, the ear, and also the T617 MIRROR sign already mentioned above the eye area, and an element curving backwards, possibly representing fur. It also bears a bar-and-dot numeral, possibly ‘7’ (or ‘8’, since there is damage to the surface of the axe where an additional dot could have been present), likely as a means of indicating the presence of the expression read as 7AN, associated with divine impersonations (Houston and Stuart 1996, 1998; Knub, Thun, Helmke 2009). The example on Figure 3D is found an another inscribed slate disk found at the site of El Tres, Costa Rica: it exhibits a prominent eye, the ear, both sets of upper and lower front teeth, the beard-like or chops-like component, a backward-pointing element possibly representing fur, and the T617 MIRROR sign. Figure 3E shows the example from the Hombre de Tikal statuette, showing the powerful curved jaw, the upper front teeth, the eye, part of the ear, and the conflated T617 MIRROR sign above the eye. Figure 3F shows an instance from a Olmec-style jade maskette at the Brooklyn Museum of Art that bears a Mayan text on the reverse: it bears both upper and lower front teeth, the eye, the eyelid/eyebrow, the ear, the diagonal line of the T617 MIRROR sign has been conflated, and a spiral- or volute-like component, perhaps corresponding to the whiskers or the beard- or chop-like component, is seen to the right or the jaw.Figure 3G shows an instance from an inscribed tubular jade bead discovered in the Sacred Cenote: it shows the eye, the infixed T617 MIRROR sign above the eye, the powerful, curved jaw, and two spiral- or volute-like elements. Figure 3His an example from the Dumbarton Oaks quartzite pectoral that shows the basic outline of the head, including the characteristic jaw, a pointy element that could be a tongue or a leaf at the front end of the jaw, but is otherwise devoid of other elements. Figure 3I is a case from the Early Classic Quirigua Monument 6 that shows most of the traits already noted, but also shows the trio of spots. Figures 3J and 3K are Late Classic examples showing the infixed T281 K’ANsign; this design was innovated during the Early Classic, appearing as early as Tikal Stela 39 (CE 376), but was not used with consistency until the Late Classic. It functions as a likely semantic classifier (Mora-Marín 2008): scribes inserted it optionally to specify which type of gopher was depicted by T757, but it had no bearing on the sign’s orthographic function and value. The example on Figure 3J shows a tongue and what appears to be a root, while that on Figure 3Kshows a tongue and a possible leaf. By the beginning of the Late Classic scribes decreased the size of the sign’s jaw. Figures 3L and 3M are codical versions, one both showing an infixed T841 7AK’AB’ for 7ahk’ab’ ‘night, darkness’, the first of which shows the T281 sign, while the second does not. The T841 graphic infix is probably comparable, in function, to T281: scribes optionally incorporated this sign into the head signs shaped like some mammals (e.g. bats), possibly to point to their nature as non-human animals (Hopkins 1994; Hopkins and Josserand 1999) or as nocturnal animals (Houston, Stuart, and Taube 2006:14) and thus functioned as semantic classifiers.

Figure 3

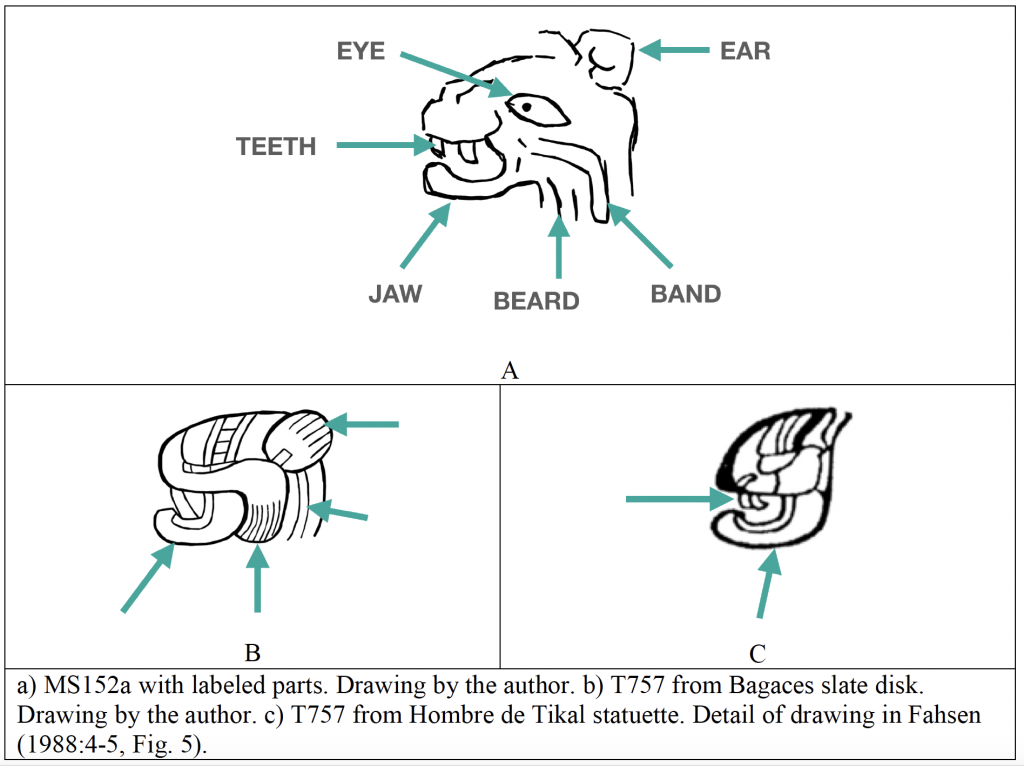

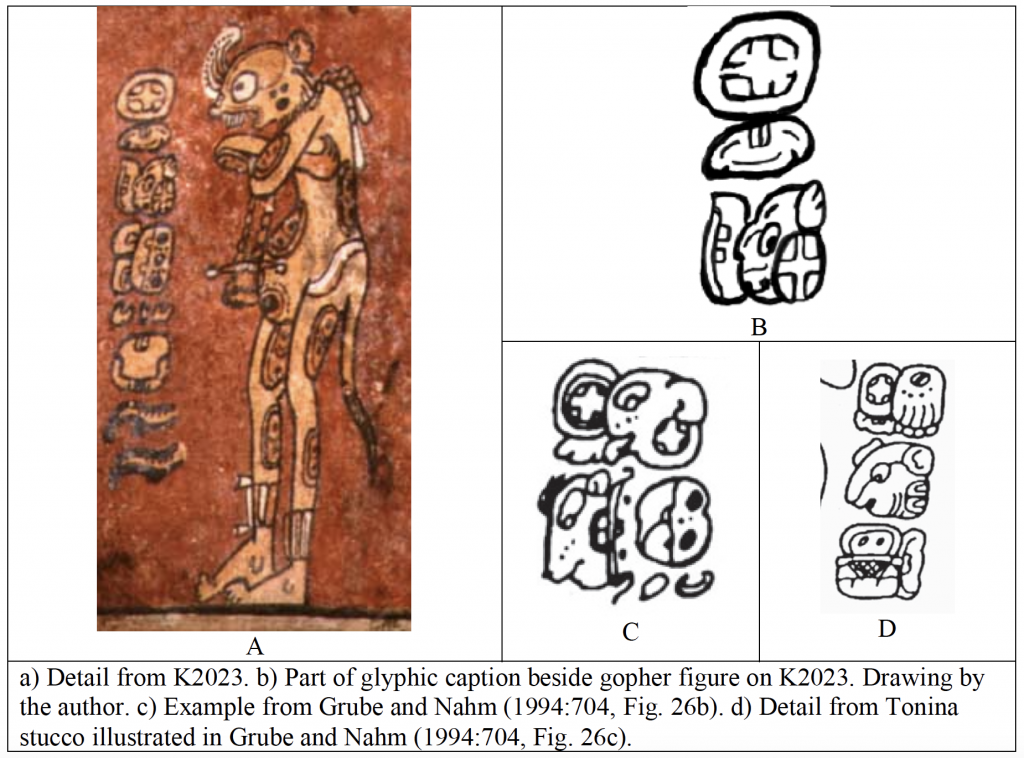

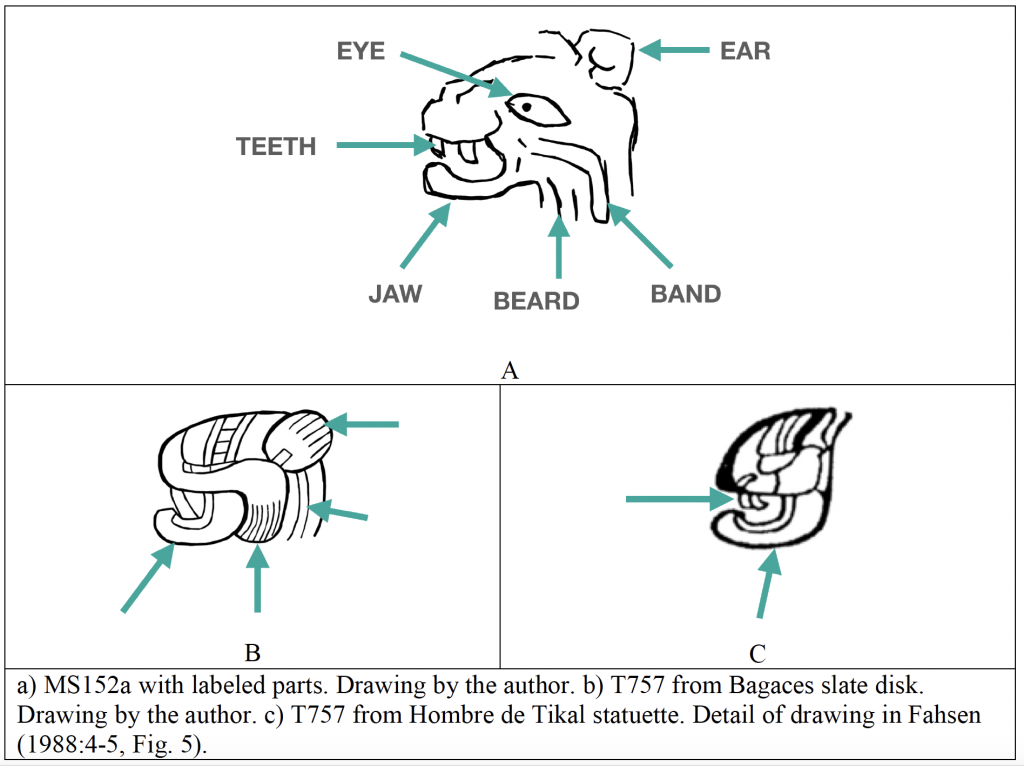

I return now to MS152a, the putative GOPHER sign in Isthmian writing. The basic components of the sign are labeled in Figure 4A, including a band-like component, a beard-like or chops-like component, and also a prominent, curved jaw. These components have already been described for several of the Early Classic Mayan examples, such as those in Figures 4B-C. What MS152a lacks, especially, is the diagonal band associated with T617 WIN ‘eye, face’ (Mora-Marín 2012), which has no place here, since in Mayan writing it is a separate sign used in the spelling of a sequence WIN-b’ah orWIN:b’ah or [WIN]b’ah for ‘eye/face=face/head’, functioning as a type of compound, possibly, referring to ‘portrait’. In fact, the early examples of Mayan T757 did not bear such MIRROR sign in cases where it was used simply for its syllabographic value b’a. The lone example of MS152a thus cannot be compared contextually, and there is no reason why one would expect the MIRROR sign to be present in it. Otherwise, the two signs are very similar.

Figure 4

To conclude, it would appear that Mayan T757 and Isthmian MS152a both represent the same entity, a pocket gopher. In the Mayan case, at least, this identity served as the basis for the acrophonic derivation of its syllabographic value b’a (based on b’aah > b’ah ‘gopher’), although in most instances the sign is likely used as a CVC syllabogram b’ah or symbolic (non-iconic) logogram B’AH to represent reflexes of Proto-Mayan *b’ah and *b’aah mentioned above, with only a few instances of its use as an iconic logogram B’AH to represent a reflex of Proto-Mayan *b’a7h ‘gopher’. It remains to be seen whether the iconographic nature of MS152a played a role in its proposed logographic/lexical value (i.e. ‘eat(ing)’) by Kaufman and Justeson (2001), or whether it is merely the result of an association with the prominent jaw and teeth of the gopher.

References

Bricker, Victoria R. 1986. A Grammar of Mayan Hieroglyphs. New Orleans: Middle American Research Institute.

Fahsen, Federico. 1988. A New Classic Maya Text from Tikal. Research Reports on Ancient Maya Writing 17. Washington, D.C.: Center for Maya Research.

Grube, Nikolai, and Werner Nahm. 1994. A Census of Xibalba: A Complete Inventory of “Way” Characters on Maya Ceramics. In The Maya Vase Book: A Corpus of Rollout Photographs of Maya Vases, edited by Justin Kerr, pp. 686–715. New York: Kerr Associates.

Hopkins, Nicholas A. 1994. Days, kings, and other semantic classes marked in Maya hieroglyphic writing. Paper presented to the American Anthropological Association, Annual Meeting, November 30–December 1, Atlanta, Georgia.

Hopkins, Nicholas A., and J. Kathryn Josserand. 1999. Issues of Glyphic Decipherment. Paper presented to the symposioum “Maya Epigraphy—Progress and Prospects,” Philadelphia Maya Weekend, University Museum, Philadelphia, April 11, 1999.

Houston, Stephen, and David Stuart. 1996 Of gods, glyphs, and kings: divinity and rulership among the Classic Maya. Antiquity 70:289-312.

—–. 1998. The ancient Maya self: personhood and portraiture in the Classic period. Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics33:73-102.

Houston, Stephen, David Stuart, and Karl Taube. 2006. The Memory of Bones: Body,

Being, and Experience among the Classic Maya. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Hunn, Eugene S. 1977. Tzeltal Folk Zoology: The Classification of Discontinuities in Nature. New York, San Francisco, London: Academic Press.

Justeson, John. 1989. The Representational Conventions of Mayan Hieroglyphic Writing. In Word and Image in Maya Culture. Explorations in Language, Writing, and Representation, edited by William F. Hanks and Don S. Rice, pp. 25-38. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

Justeson, John S., and Terrence S. Kaufman. 1993. A Decipherment of Epi-Olmec Hieroglyphic Writing. Science 259: 1703–1711.

—–. 1997. A Newly Discovered Column in the Hieroglyphic Text on La Mojarra Stela 1: A Test of the Epi-Olmec Decipherment. Science 277:207-210.

Kaufman, Terrence, and John Justeson. 2001. Epi-Olmec Hieroglyphic Writing and Texts. Austin: Texas Workshop Foundation.

—–. 2004. Epi-Olmec. In: The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World’s Ancient Languages, edited by Roger D. Woodard, pp. 1071-1108. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kaufman, Terrence, with John Justeson. 2003. Preliminary Mayan Etymological Dictionary. http://www.famsi.org/reports/01051/index.html.

Macri, Martha J., and Matthew Looper. 2003. The New Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs. Volume One: The Classic Period Inscriptions. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Macri, Martha J., and Gabrielle Vail. 2009. The New Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs. Volume Two: The Codical Texts. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Macri, Martha J., and Laura Stark. 1993. A Sign Catalog of the La Mojarra Script. Monograph 5. San Francisco: Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute.

Mora-Marín, David F. 2008. Full Phonetic Complementation, Semantic Classifiers, and Semantic Determinatives in Ancient Mayan Hieroglyphic Writing. Ancient Mesoamerica 19:195-213.

—–. 2012. The Mesoamerican Jade Celt As ‘Eye, Face’, and the Logographic Value of Mayan 1M2/T121 as WIN ‘Eye, Face, Surface’. Wayeb Notes 40.

—–. 2018. The Hatzcap Ceel Axe Inscription: Recent Documentation and Epigraphic Analysis. Glyph Dwellers Report 60:1-24.

Nehammer Knub, Julie, Simone Thun, and Christophe Helmke. 2009. The Divine Rite of Kings: An Analysis of Classic Maya Impersonation Statements. In The Maya and their Sacred Narratives: Text and Context in Maya Mythologies, edited by Geneviève Le Fort, Raphaël Gardiol, Sebastian Matteo, and Christophe Helmke, pp. 177-195. Markt Schwaben: Verlag Anton Saurwein. Acta Mesoamericana, vol. 20.

Schele, Linda. 1990. Ba as “First” in Classic Period Titles. Texas Notes on Pre-Columbian Art, Writing, and Culture 5.

Winfield Capitaine, Ferdinand. 1988. Research Reports on Ancient Maya Writing 16: 1-36.

[i] Bricker’s (1986) proposal that T757/AP9 is used to spell a verb of motion attested in Tzeltalan, *b’ah(t) ‘to go’, has not been supported by subsequent research.

[ii] I utilize Kaufman with Justeson (2003) for Proto-Mayan etyma.