A Previously Unidentified Example of T1/HE6 ʔu on the Painted Stone Block from San Bartolo Sub-V

David F. Mora-Marín

davidmm@unc.edu

University of North Carolina

Chapel Hill

12/12/2020

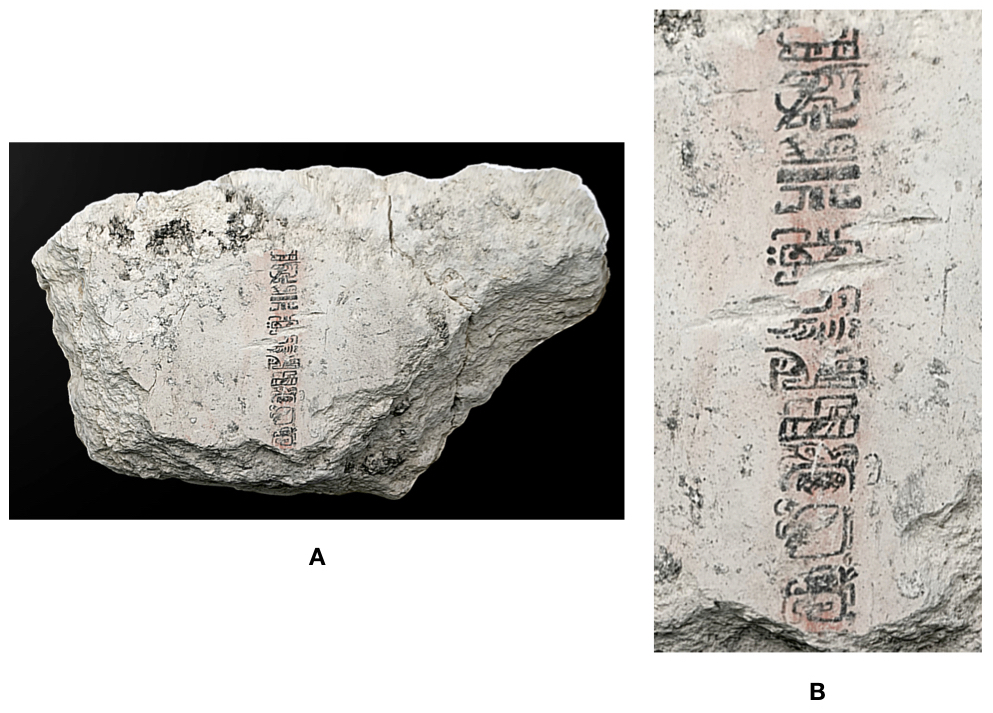

This is a very brief note on the identification of a previously unnoticed sign on the famous painted stone block from San Bartolo Sub-V published by Saturno, Stuart, and Beltrán (2006), who date it to ca. 300-200 BCE. The San Bartolo project website maintains a link to a downloadable version of the article, here (select “PDF” button instead of “View Full Text” link). The drawing of the painted text is on page 1282 of that document. Glyph block 8 is the one that concerns this post. In it one finds at least two signs: a sign that resembles a bird facing to the left, and underneath it, a sign that resembles T602/XD1, the syllabogram pa. (See Thompson (1962) or “T-number” numeric codes, and Macri and Looper (2003) for alphanumeric sign catalog codes.) To the right of these two signs, the drawing by David Stuart shows what can only be described as a squiggly motif, resembling a tail.

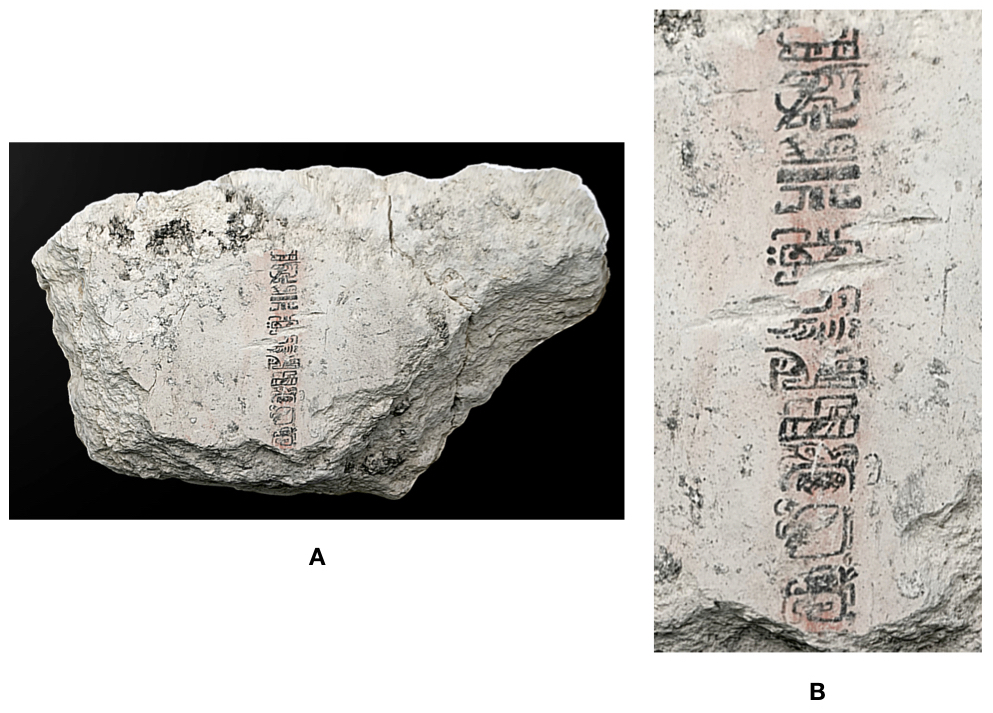

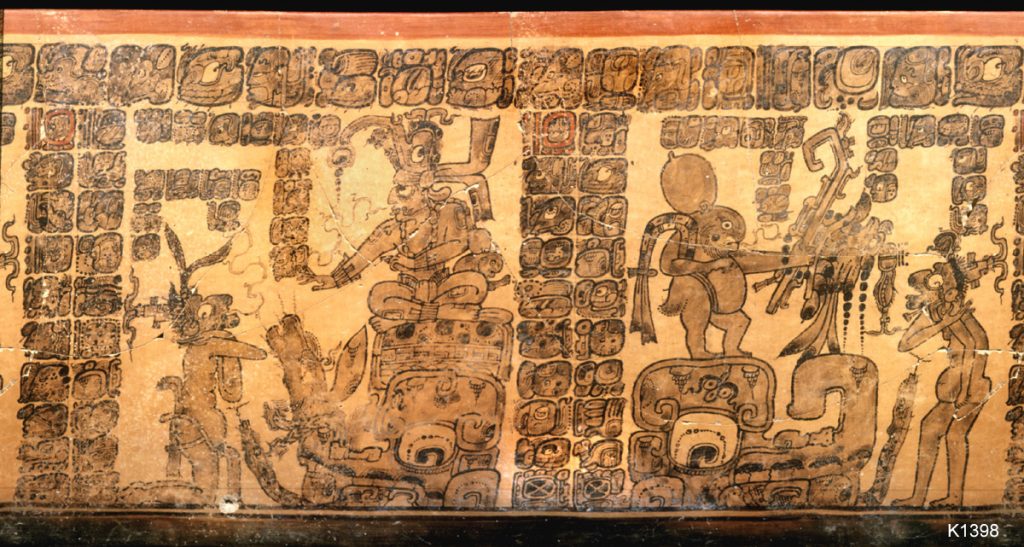

Recently, Alexandre Tokovinine prepared a high-resolution orthomosaic of the block, which constitutes “a 3D-model-based combo of overlapping photographs reflecting average values of overlapping pixels” (Tokovinine, personal communication, 12/11/20). The image, brought to my attention by Dana G. Moot II, was published online 2/13/18 (Tokovinine 2018). Figure 1 presents a screenshot, but the reader may consult the original here.

Figure 1

I decided to take a close look at Tokovinine’s rendering of this remarkable text, in connection with a project on the paleography of T1/HE6 ʔu. Initially I was interested in a sign on Glyph block 4 that resembles two dots, as some Late Preclassic texts exhibit a similar sign, and in at least two of them, the sign in question can be argued, on the basis of contextual similarities with later texts, to be functioning to spell u-, the third person singular ergative/possessive proclitic (e.g. Mora-Marín 2001, 2008a, 2010). However, in my opinion, and despite a few discussions of this text besides the original report (e.g. Skidmore 2006; Mora-Marín 2008b; Giron-Ábrego 2012), there is still no good evidence to settle on a particular interpretation of the TWO.DOTS sign on the San Bartolo painted block.

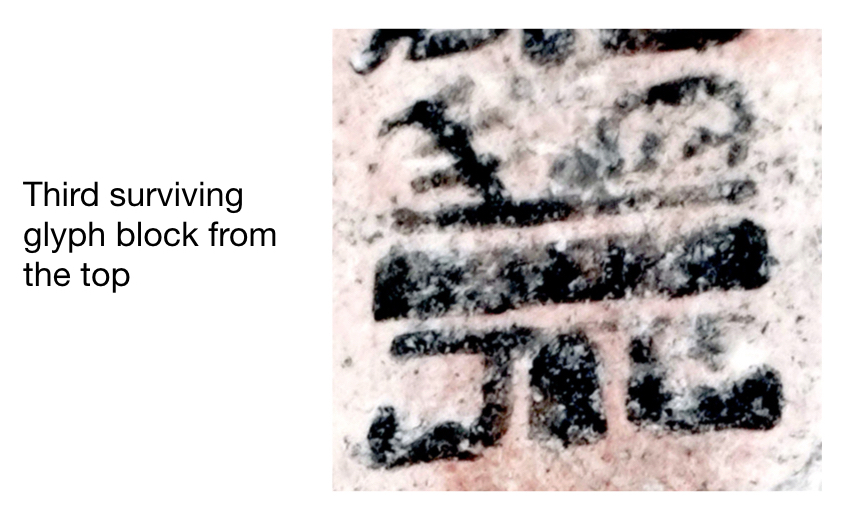

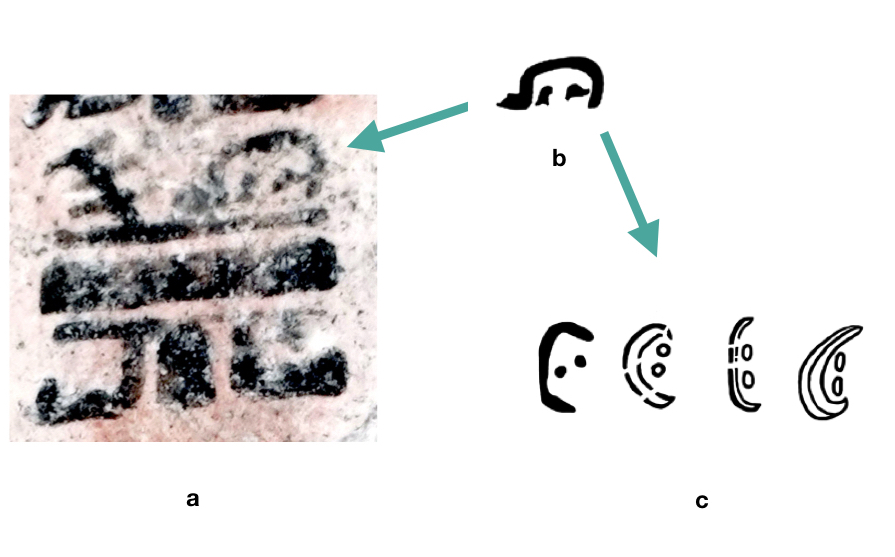

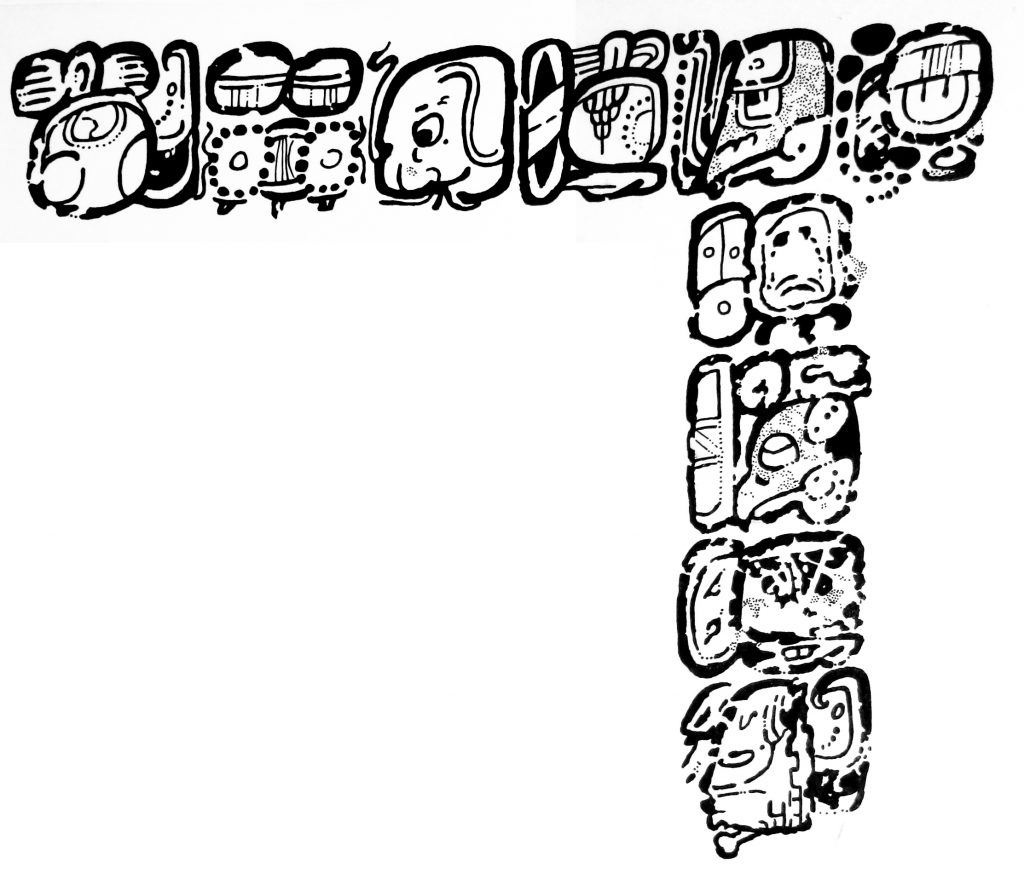

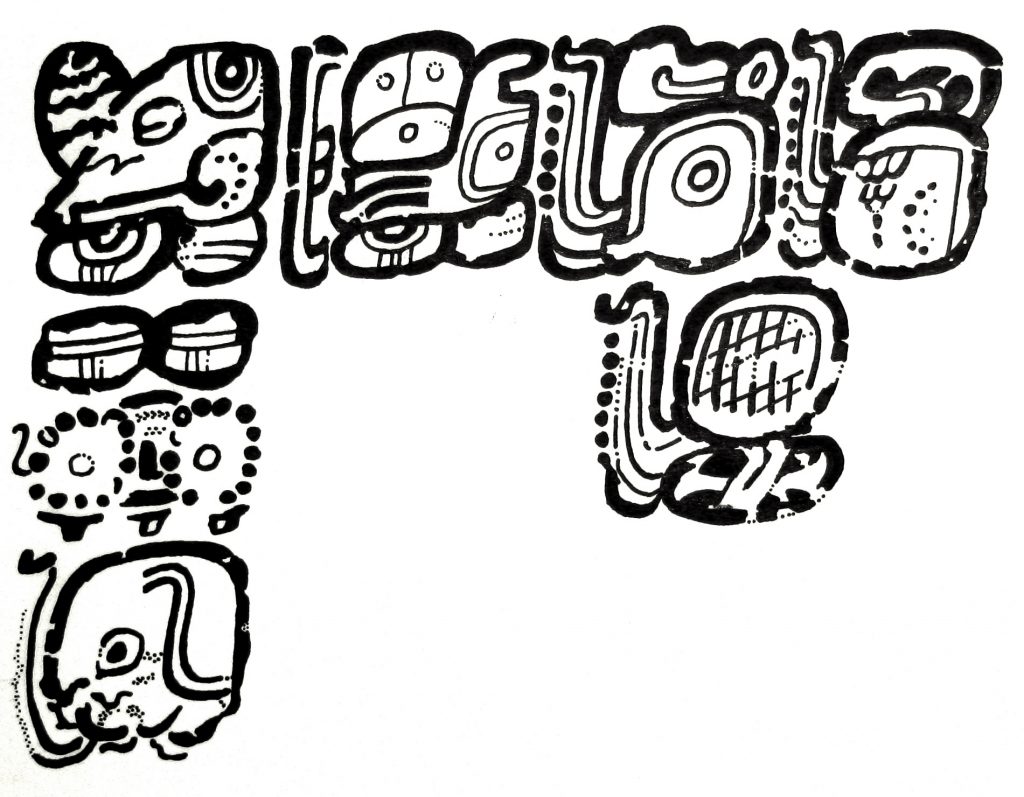

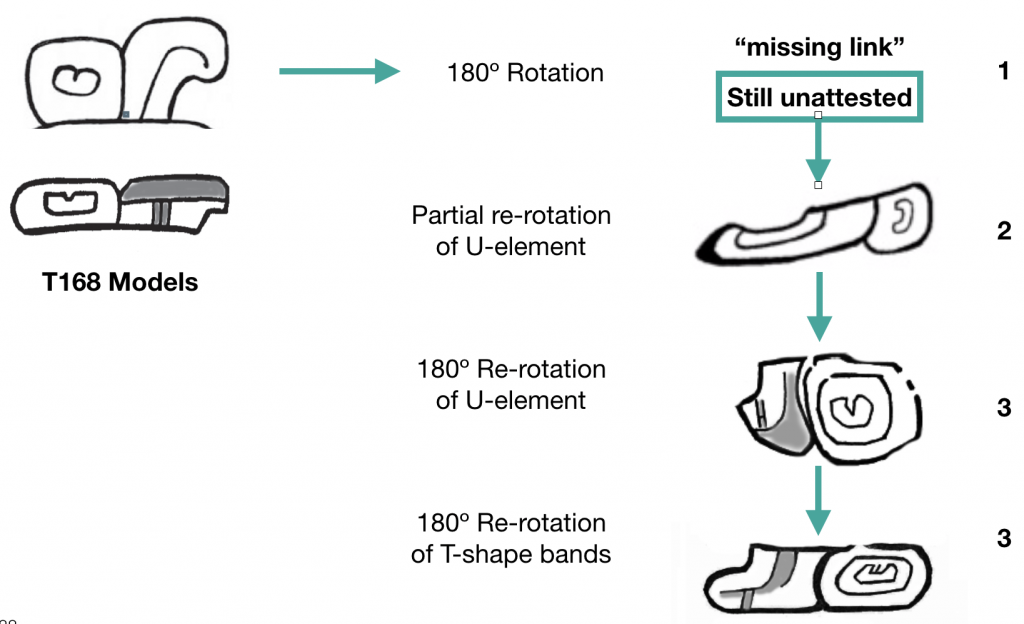

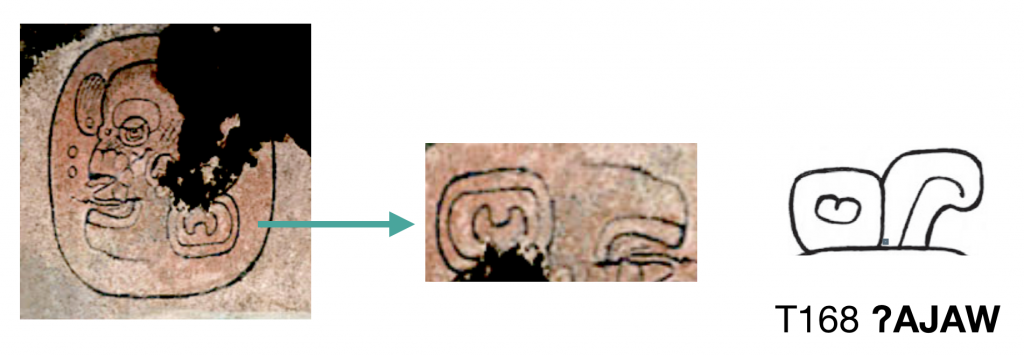

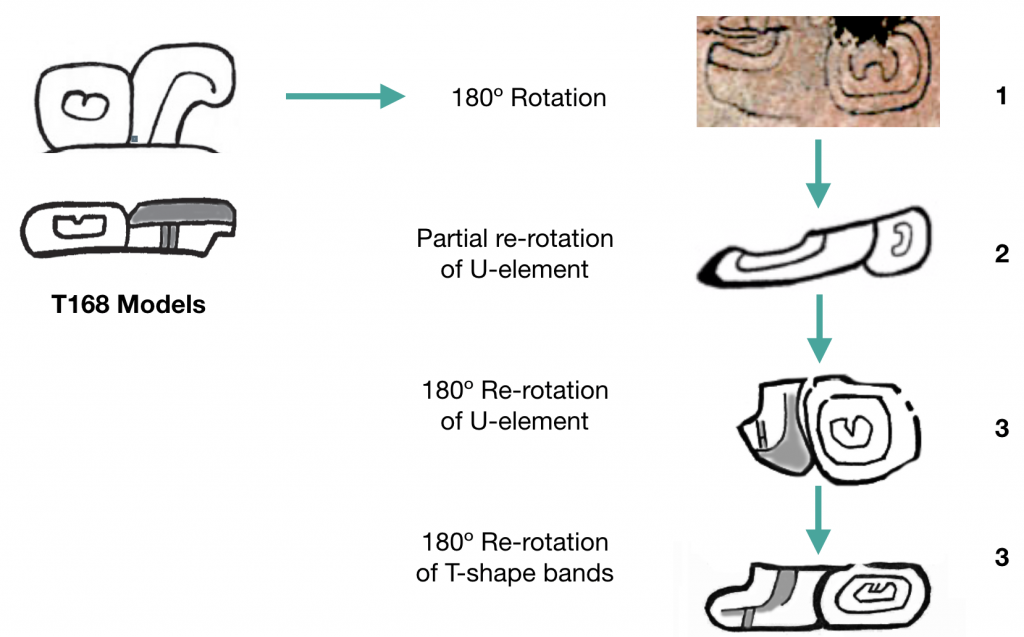

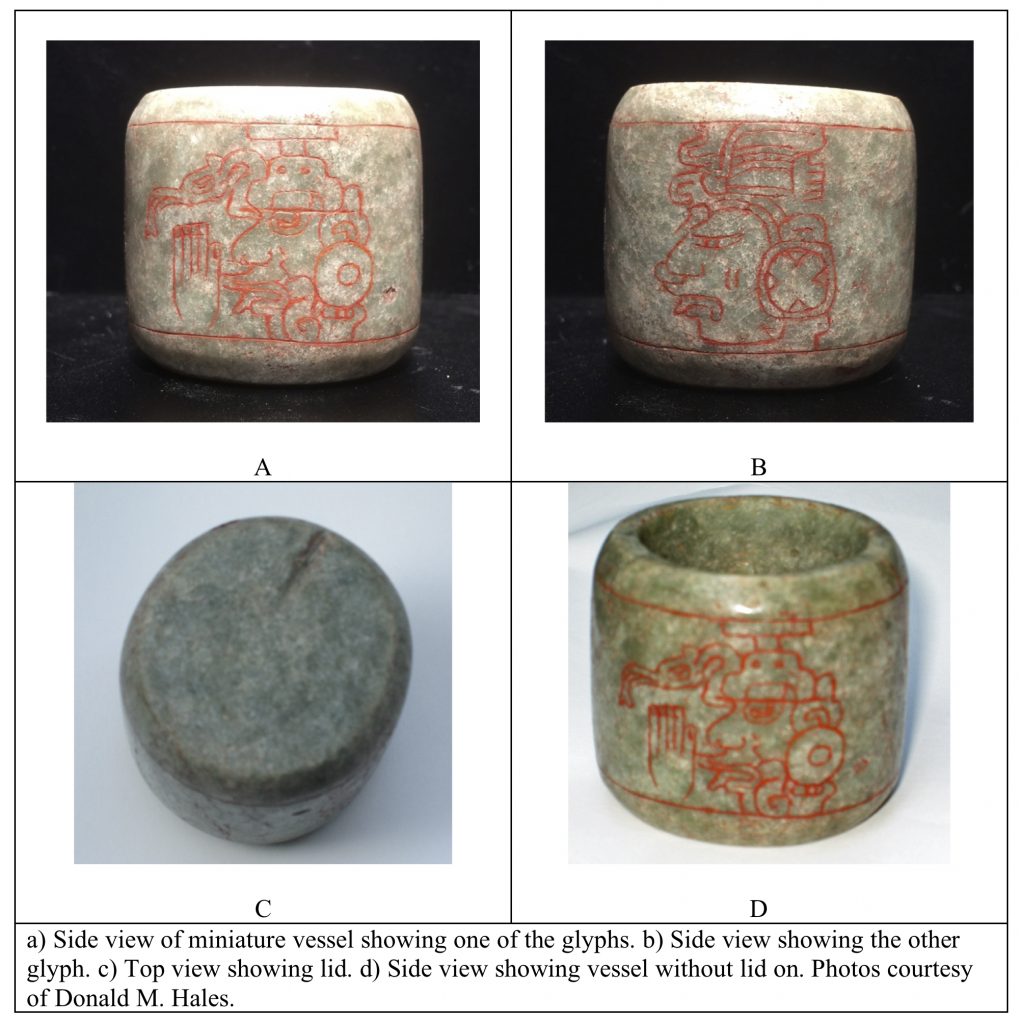

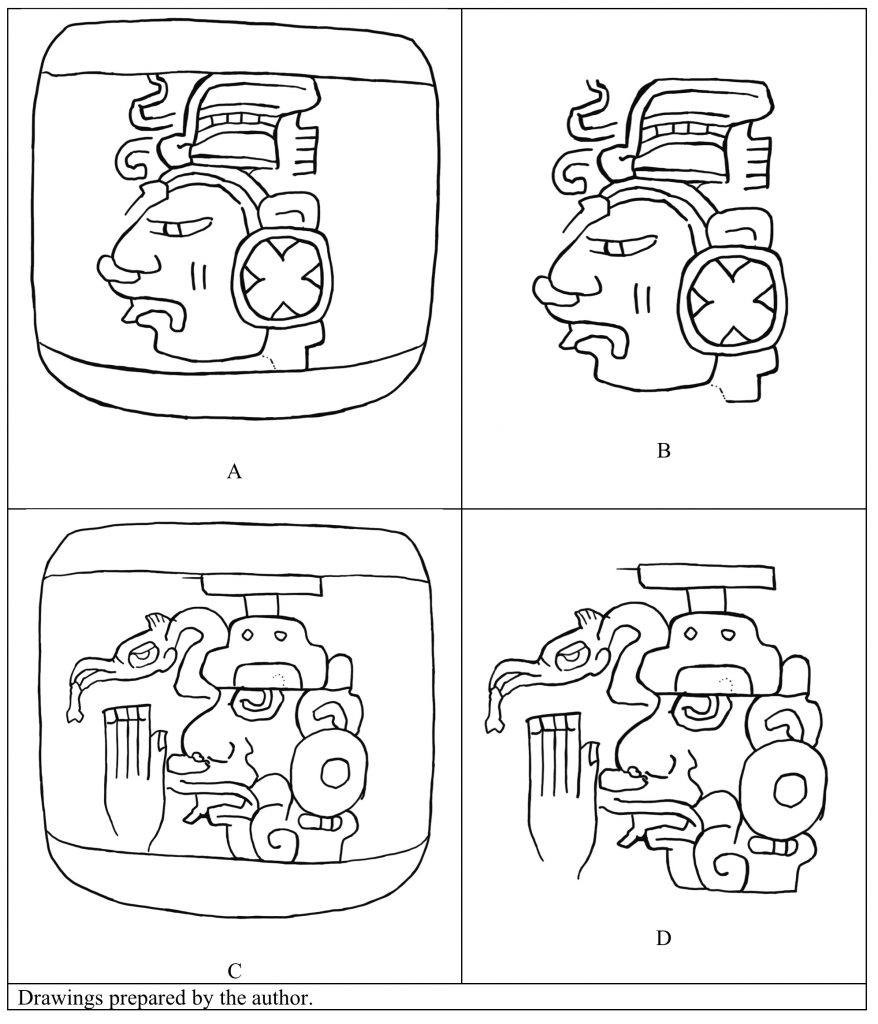

Despite this negative assessment, I noticed something else on Tokovine’s photomosaic that I did not expect: when I turned my attention to the element rendered as a squiggly motif in David Stuart’s drawing, I realized that it is not a squiggly motif at all, but an example of T1/HE6 ʔu corresponding to the design present on two very early portable texts lacking calendrical information but which I and others have stylistically assigned to the Late Preclassic or Protoclassic period. Table 1 lists the relevant unprovenienced texts, an Olmec-style pectoral mask at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, and a fragmentary tubular jade bead found in the Sacred Cenote of Chichen Itza, along with some of the previous discussions and relative stylistic datings. The rendering of this sign on the San Bartolo stone block as a squiggly, tail-like element was probably by a crack or fracture on the stone, visible in Tokovinine’s scan. Figure 2A shows a screenshot of Glyph block 8 from the painted San Bartolo stone block, captured from the photomosaic by Tokovinine, with an arrow pointing to the sign that corresponds to the design of T1/HE6 ʔu present on the two Late Preclassic or Protoclassic texts in question (Figures 2B-C). The same design of T1/HE6 appears on one of the Group 4 texzts from Jolja Cave in Chiapas (Sheseña 2007:4, Fig. 3).

Table 1

Figure 2

One more issue deserves attention. In their description of the text’s discovery and dating, Saturno et al. (2006:1282) state the following:

In their overall appearance, the text bears some resemblance to the so-called Epi-Olmec script used by neighboring peoples to the west during the Late Preclassic and Early Classic periods […]. All examples of that script postdate the San Bartolo block, however, raising the question of the direction in which any influence may have flowed.

First, I would like to comment on the fact that there is in fact at least one Epi-Olmec text that could predate or be co-eval with the San Bartolo painted block: the Chiapas de Corzo sherd can be dated to ca. 400-150 BCE (Francesa Phase) or 150-0 BCE (Guanacaste Phase) based on its contextual associations, recently reviewed by Macri (2017:2), but dating specifically to Francesa phase according to some authors (Kaufman and Justeson 2001:2, 2008:56). Second, the odd placement of the T1/HE6 ʔu sign on the San Bartolo text, should it be there to spell a proclitic u-, could point to a different interpretation of the direction of influence. In the text incised on the tubular jade bead found in the Sacred Cenote, the location of T1/HE6 on the right side of two glyph blocks makes sense in terms of visual conventions: the profile head glyphs are in both cases facing to the right, and thus the intra-glyph block reading order is right-to-left. In contrast, on the painted stone block from San Bartolo, the portrait head glyphs are facing to the left, leaving no visual justification for the placement of T1/HE6 to the right. Instead, I offer a different possibility.

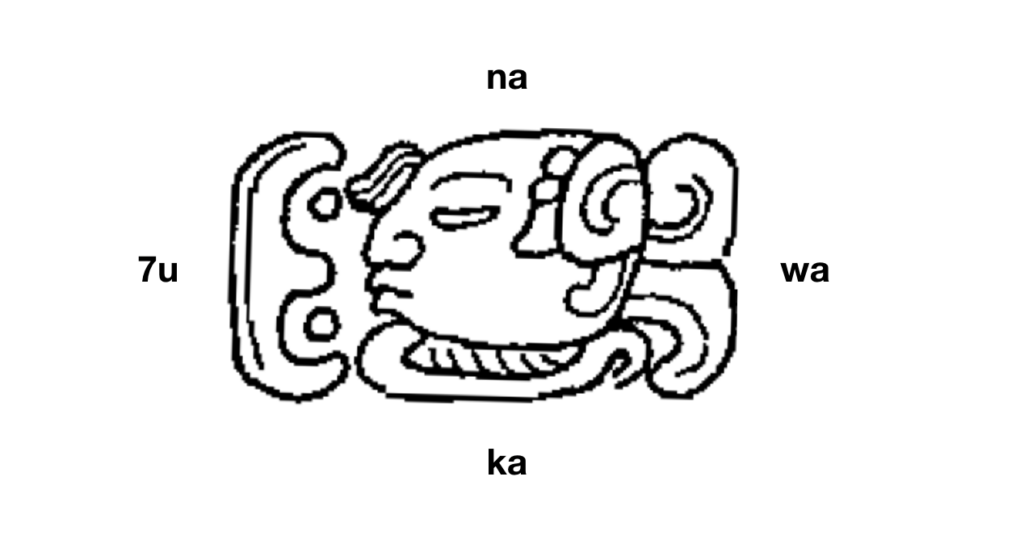

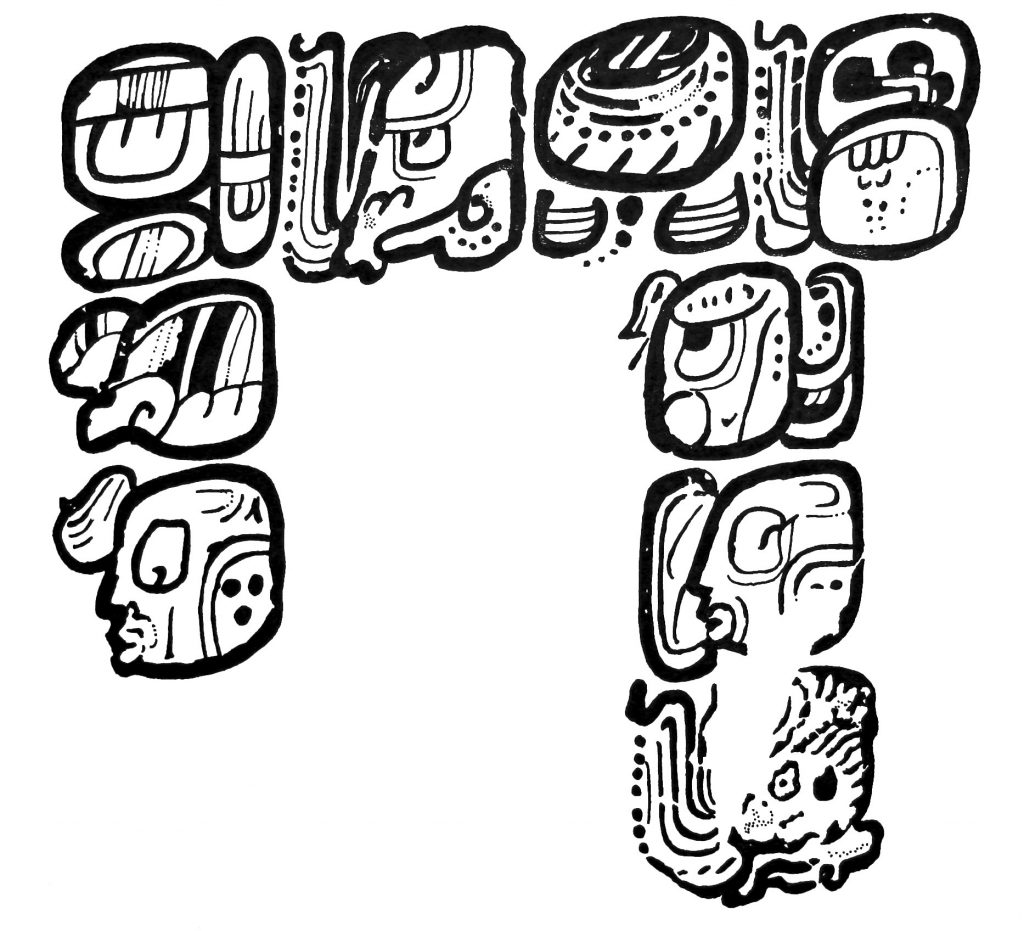

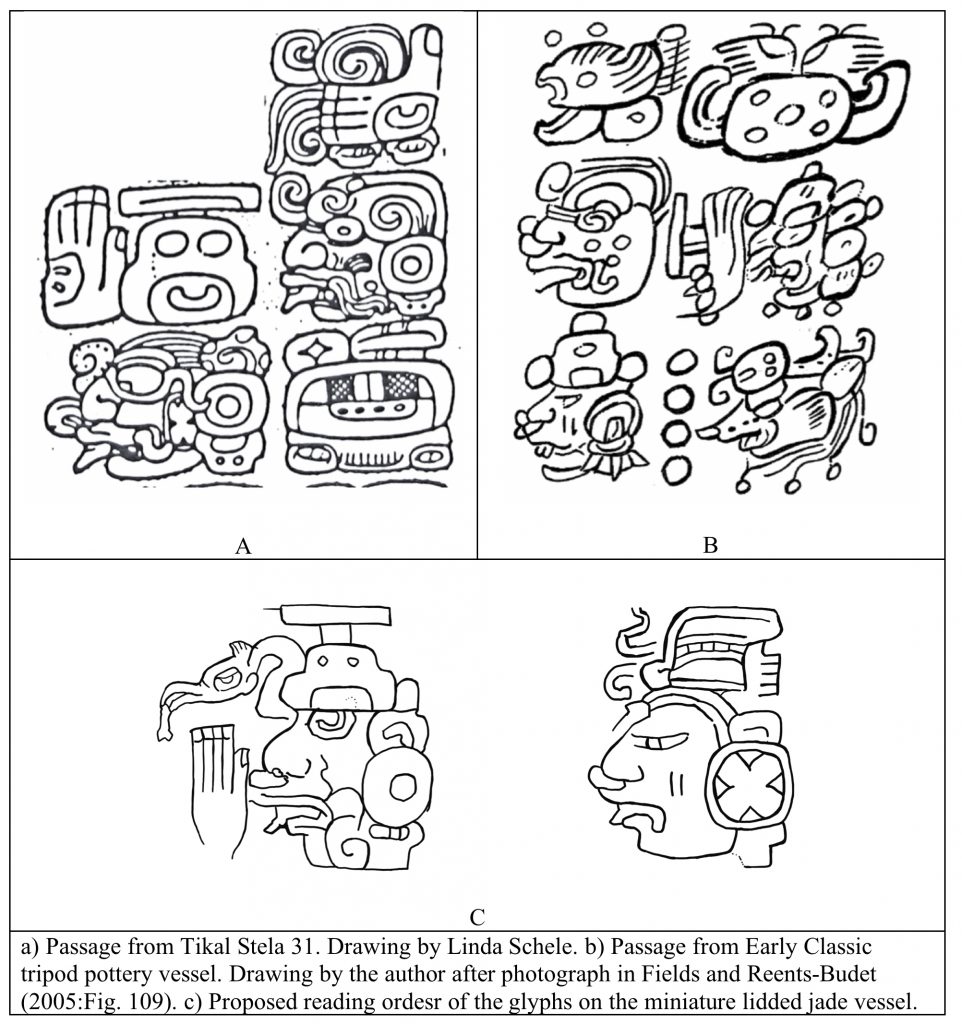

Mora-Marín (1996, 1997, 2001a, 2010) has previously discussed possible cases of grapheme diffusion between Mayan and Epi-Olmec scribes involving syllabograms, one of these being possibly Epi-Olmec MS20 wʉ, seen in Figure 3A, and Mayan T1/HE6 ʔu. The design present on the painted stone block from San Bartolo and the other texts discussed earlier, two examples of which are seen in Figure 3B, resembles the design of MS20 wʉ, whose typical functions in Epi-Olmec writing, according to Justeson and Kaufman (1993, 1997) and Kaufman and Justeson (2001, 2004) include word- and phrase-final markers, namely, the independent completive verbal suffix -wʉ, and the relativizer -wʉʔ. If Mayan scribes did in fact borrow T1/HE6 ʔu from Epi-Olmec scribes, perhaps for the purpose of spelling the high-frequency grammatical morpheme u-, a vowel-initial proclitic whose pronunciation would resemble the initial /w/ of the Epi-Olmec syllabogram wʉ, then the stone block in question could be evidence of such influence already by 300-200 BCE.[1] In other words, Epi-Olmec MS20 wʉ may have sounded very close to a non-phrase or word-initial /u-/ marker in Mayan, and Mayan scribes may have borrowed it to spell such marker.[2] But this is speculation at this point, worthy of a blog post, but requiring more evidence for substantiation.

Figure 3

For now, what is important to highlight is the attestation of this design of T1/HE6 ʔu, possibly the earliest design of such grapheme, by ca. 300-200 BCE, on the San Bartolo Sub-V painted stone block. The possibility of Epi-Olmec/Mayan diffusion raised here will require additional data, data that may very well be uncovered at the site of San Bartolo in the near future.

Acknowledgments. I would like to thank Dana G. Moot II for his email correspondence on the available drawings of the painted stone block from San Bartolo, and for calling my attention to Alexandre Tokovinine’s scan. I am indebted to Alexandre Tokovinine for the information provided on his scan of the text in question.

References

Fields, Virginia, and Dorie Reents-Budet. 2005. Lords of Creation: The Origins of Sacred Maya Kingship. London: Scala Publishers Limited.

Giron-Ábrego, Mario. 2012. An Early Example of the Logogram TZUTZ at San Bartolo. Wayeb Notes 42.

Justeson, John, and Terrence Kaufman. 1993. A Decipherment of Epi-Olmec Hieroglyphic Writing. Science 259:1703-1710.

—–. 1997. A Newly Discovered Column in the Hieroglyphic Text on La Mojarra Stela 1: A Test of the Epi-Olmec Decipherment. Science 277:207-210.

Kaufman, Terrence. 2020. Olmecs, Teotihuacaners, and Toltecs: Language History and Language Contact in Meso-America. URL: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340721651_MALP_2020?channel=doi&linkId=5e9a4336299bf13079a24ec9&showFulltext=true.

Kaufman, Terrence, and John Justeson. 2001. Epi-Olmec hieroglyphic writing and texts. Austin: Texas Workshop Foundation.

—–. 2004. Epi-Olmec. In The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World’s Ancient Languages, edited by Robert D. Woodard, pp. 1071-1108. Cambridge University Press.

—–. 2008. The Epi-Olmec Language and its Neighbors. In Classic Period Cultural Currents in Southern and Central Veracruz, edited by Philip J. Arnold, III, and Christopher A. Pool, pp. 55–83. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

Macri, Martha J. 2017. Isthmian Script at Chiapa de Corzo. Glyph Dwellers 56.

Macri, Martha J., and Matthew Looper. 2003. The New Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs. Volume One: The Classic Period Inscriptions. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Mora-Marín, David F. 1996. The Social Context for the Origins of Mayan Writing: The Formative Ceremonial Complex, Portable Elite Objects, and Interregional Exchange. Unpublished Senior Honors Thesis on file in the Anthropology Department at The University of Kansas, Lawrence.

—–. 1997. The origins of Maya writing: The case for portable objects. In Tom Jones and Carolyn Jones (eds.), U Mut Maya VII, 133-164. Arcata: Humboldt State University.

—–. 2001a. The Grammar, Orthography, and Social Context of Late Preclassic Mayan Texts. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis. University at Albany, Albany, New York.

—–. 2001b. Late Preclassic inscription documentation (LAPIDA) project. Retrieved from: http://www.famsi.org/reports/99049/99049MoraMarin01.pdf.

—–. 2008a. Análisis epigráfico y lingüístico de la escritura maya del período Preclásico Tardío: Implicaciones para la historia sociolingüística de la region. In Juan Pedro Laporte, Bárbara Arroyo, and Héctor E. Mejía (eds.), XXI Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2007, 853-876. Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología.

—–. 2008b. Two Parallel Passages from the Late Preclassic Period: Connections Between San Bartolo and An Unprovenanced Jade Pendant. Wayeb Notes 29:1-6.

—–. 2010. La epigrafía y paleografía de la escritura preclásica maya: nuevas metodologías y resultados preliminares. In Bárbara Arroyo, Adriana Linares Palma, and Lorena Paiz Aragón (eds.), XXIII Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2009, 1045-1057. Guatemala City, Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología.

—–. 2016. Testing the Proto-Mayan-Mije-Sokean Hypothesis. International Journal of American Linguistics 82:125-180.

Proskouriakoff, Tatiana. 1974. Jades from the Cenote of Sacrifice, Chichén Itzá, Yucatán. Peabody Museum Memoirs, Vol. 10, No. 1. Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Saturno, William A., David Stuart, and Boris Beltrán. 2006. Early Maya Writing at San Bartolo, Guatemala. Science Magazine: Science Express, pp. 1-6.

Schele, Linda, and Mary E. Miller. 1986. The Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art. New York: George Braziller, Inc., in association with the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth.

Sheseña, Alejandro. 2007. Los textos jeroglíficos mayas de la cueva de Jolja, Chiapas. Artículos de Mesoweb. Mesoweb: www.mesoweb.com/es/articulos/jolja/Jolja.pdf.

Skidmore, Joel. 2006. Evidence of Earliest Maya Writing. URL: http://www.mesoweb.com/reports/SanBartoloWriting.html.

Thompson, Eric J. 1962. A Catalogue of Maya Hieroglyphics. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Tokovinine, Alexandre. 2018. “Painted inscription, San Bartolo.” Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution. URL: https://skfb.ly/6VzQF.

Zavala Maldonado, Roberto. 2007. Las cláusulas de relativo en lenguas cholanas, un calco zoqueano. Paper presented at CILLA III, Austin, Texas, October 25-27, 2007.

[1] The vowel of Epi-Olmec MS20 wʉ that might have been perceived by Mayans as [a], [ə], or [u], depending on the particulars of the language and the context Evidence for Mixe-Zoquean /ʉ/ being borrowed by Mayan languages as [a] can be found in the borrowing of Proto-Mixe-Zoquean *sʉk ‘bean’ as K’iche’ sak ‘coral bean tree’ and Kachikel <sac> ‘dados; habas con que juegan los indios dados’ (Kaufman 2020:155); as [ʉ] in Zoquean *-pʉ(ʔ) ‘relativizer’ borrowed as Ch’ol and Chontal -b’ə ‘relativizer’ (Zavala 2007); and as [u] in the borrowing of Proto-Mixean *hʉ¢ ‘to grind’ and *hʉ¢-i ‘dough’ into Mayan as Western Mayan and Lowland Mayan *juch’ ‘moler’, and Proto-Mixean *mʉkʉk ‘strength’ as Greater Lowland Mayan *muq’ ‘strength’ (Mora-Marín 2016).

[2] A phrase- or word-initial /u-/ would be realized phonetically as [ʔu-]. In fact, the pronunciation of such marker, by far the most frequent motivation for the use of T1/HE6 ʔu, could have led to scribes reanalyzing it orthographocally as ʔu.